Первый слайд презентации: The history of ancient ROMAN law

PhD in Law Trikoz E.N. © 2023

Слайд 3

Roman law, issues of its development & reception is a subject of particular interest for many generations of historians and jurists. Special attention is given to the classical period in the development of Roman law ( I B.C. - III A.D.), when owing to the prominent role of eminent lawyers many legal concepts, developed yet in archaic Roman law, were systematized and deepened. C lassical Roman lawyers made the totality of these notions into the mobile legal system, which gained the authority of unsurpassed model. In this case the decisive importance among the reasons causing to life the phenomenon of the Roman classical law was the wide spread of commodity production and commodity-money relations.

Слайд 5

I. The classical form of Roman law was a consequence of significant changes in its content. R eligious ritualism, symbolism, and strict formalism disappeared from Roman law. It became fully secular in nature, and the legal prescriptions were no longer enforced by religious, but by secular state sanctions. Classical Roman law was no longer based on religious traditions and customs, but on a rationalistic worldview and the doctrine of natural law ( Latin jus naturale ). Roman jurists understood it as that which corresponds to natural reason, to the principles of morality and ethical justice which establish general principles of existence for all peoples and human beings. E.g., all human beings are equal and born free ; all Roman citizens are equal before the law according to the principle of justice ( Latin aequitas ); the human person deserves respectful treatment based on the principle of humanity ( Latin humanitas ). Roman Law of the Classical period ( I B.C. - III A.D. ) acquires the following distinctive features :

Слайд 6

II. The rigorism of the Roman law was weakening and its plasticity and adaptability, its ability to quickly respond to the new demands of life, was gaining priority. In the constructions of the Roman jurists, the logical consistency of law was combined with the real needs of life. III. There are significant changes in the structure of Roman law and monolithic and unquestionable authority of old civil law leaves the historical scene. N ew historical systems of law are formed, dualism in Roman law manifests itself. Thus, the distinction between public and private law ( Latin jus publicum – jus privatum ), which will eventually become the main structural subdivision in national legal systems of today, is made more clearly in the ancient Roman legal system. The classical distinction of law within this first kind of its dualism is given by the III rd century AD Roman jurist – Ulpianus : " Public law is that which is addressed, refers to the status & condition of the Roman State; private law has in mind the benefit & advantage, the interests of individuals " ( D. 1.1.1.2 ). Domitius Ulpianus (ca. 160-228)

Слайд 7

It was during the classical period that Roman private law became more developed and adapted to the finest detail to regulate the new commodity-money relations. A unique system of arrangement in the text of private law norms was created – the Institutional System. The Roman jurist of the middle of the II century A.D. Gaius proposed the division of private law into sections concerning the personal status of individuals, property law, law of obligation and legal process ( the famous division of law into persons, things, and actions ): " Omne autem jus quo utimor vel ad personas as pertinet, vel ad res, vel ad actiones " ("All that law which we use refers either to persons, or to things, or to lawsuits "). Scholars of legal history still debate Gaius ’ role in the creation of the threefold Institutionensystem, which has so fundamentally shaped legal traditions in the West, there is no particular reason to believe that he coined the phrase iuspersonarum.

Слайд 8

The archaic, outdated provisions of the civil law ( quiritus ) gradually became apparent, as well as its unsuitability to regulate developed commodity-money relations, which was hindered in particular by its " sacredness " and the slowness of the Committees and the Senate. This is how the second type of dualism in Roman law emerged – the opposition of old civil law and mobile praetorian law ( lat. jus civile – jus praetorium ). It was the judicial magistrates, principally praetorians, who created this new historical system of law as a kind of " living voice of civil law ", supplementing and even correcting the old regulations of civil law, which were already insufficient in quantitative and qualitative terms. In addition to the civil law, a number of institutions were created by the praetors, mainly by edicts and equipped with new means of protection.

Слайд 9

But the most original phenomenon in Roman law is another of its historical systems, opposed to the civic, primordial Roman law, which is the law of nations ( lat. jus civile - jus gentium). This kind of dualism grew out of a feature of civil law such as its narrowly national scope, covering only relations between Roman citizens ( quirites ). About a hundred years after the establishment of the office of city praetor, the magistracy of praetor of peregrins ( foreigners ) appears, whose jurisdiction extended to relations between peregrins and between peregrins and Romans. The norms of the old ( Quiritian ) and new ( Praetorian ) law, as well as those of the legal systems of the peoples inhabiting the Roman Empire, which had proved their vitality, were included by the Praetor of peregrines in the Roman system of the law of nations. Gradually, praetorian law, judicial custom, and the inexhaustible activity of jurists led to the merging of civil law and the law of nations.

Слайд 10

IV. The development of Roman law in the Classical period was particularly favoured by the new interpretation of law, as well as by the rhetorical theory going back to Aristotle, which taught the logical interpretation of law. In opposition to the literal interpretation of the law, there was a requirement to identify the real will of the legislator and the goals of the law. Using the contrast between the " spirit " of the law and the " letter “ of the law, Roman lawyers were able to transform the old Quirite law and adapt it to the new historical conditions.

Слайд 11

V. Significant changes took place in the technique of expression of legal norms and legal culture as a whole. The distinctive feature of classical Roman law was the high development of its institutions, the clarity of legal norms, the accuracy of wording, the validity of decisions. Special textbooks appeared in which many legal norms and maxims of lawyers were recorded, later becoming aphorisms : "To know laws is not to hold on to their words, but to understand their power and meaning ", "It is permitted to repulse violence by force ", etc. It is possible to note two legal institutions, which in Roman law reached a full detail and a high level of legal form and technique : the institution of private property and the institution of the contract.

Слайд 12

VI. I ndividualism in Roman Law The distinguishing features of Roman classical law were the obvious individualism and even selfishness of legal prescriptions in their utmost expression and the highest freedom of self-determination rights for the richest and wealthiest of Rome's free population. Self, Society, Individual, and Person in Roman Law Roman law introduces a basic distinction between public law (that is concerned with the interests of the state) and private law (concerned with the interests of individuals). In private law, more than in the domain public law, are the most important contributions of the Roman jurists to p olitical thought : • In particular, within private law they elaborated the idea of legal limits to the extension of the power ( iurisdictio ) and the means of exercise of power by the magistrates.

Слайд 13

VII. The plurality, diversity and decentralization of the sources of Roman law, which by no means prevented its high mobility and achievement of its classical form. The norms of Roman law were formulated directly in acts passed by popular Assemblies ( Lat. l eges ), in decrees of the Senate ( senatussconsultans ), in edicts of magistrates, especially praetors, and in activities of lawyers. The latter were very active in interpreting the law and, at the same time, filling gaps in it. From the point of view of the way in which legal norms were recorded and expressed, Roman law differed from the Romano- Germanic legal system. The sources in classic period were a set of decisions of specific cases, and even collections of general rules ( Institutes, Digests, etc.), which were a further processing and generalization of the conclusions of specific court cases ( casuses ).

Слайд 14

VIII. The Roman law had already become a valid law in a number of countries of Central and Southern Europe in a number of centuries after the fall of Rome itself. Since the XIIth century one of the most important processes of the Middle Ages – reception of Roman law (Latin receptio – “acceptance”), i.e. restoration of its action, borrowing, selection, processing and assimilation. Historically, the first steps of reception are the study of Roman law by university professors (the school of glossators : Irnerius, Placentinus, Accurcius ). The main content of reception is the use of past experience in the creation of new law, as can be seen in the Napoleonic Code of 1804 or the German Civil Code of 1896.

Слайд 15

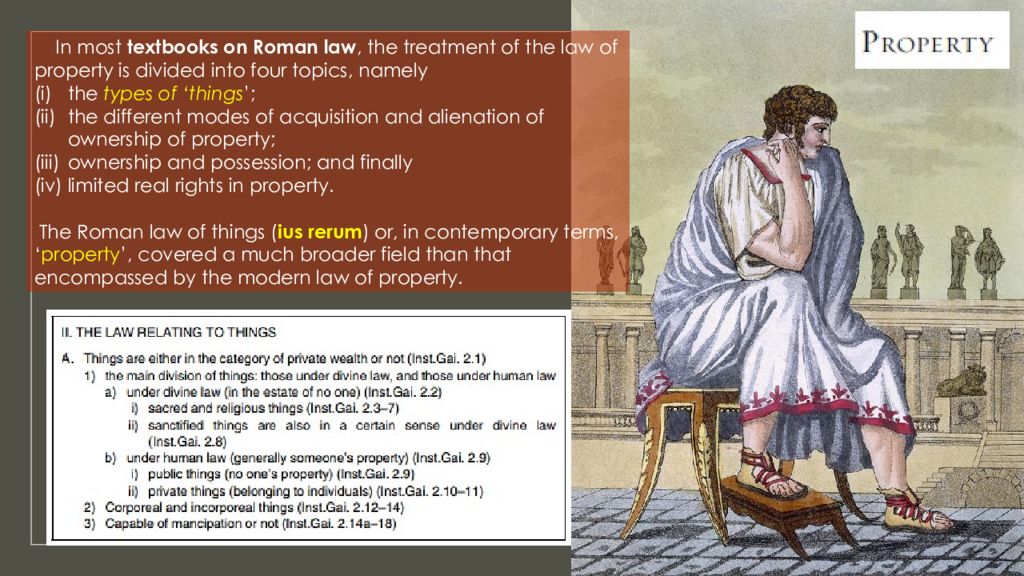

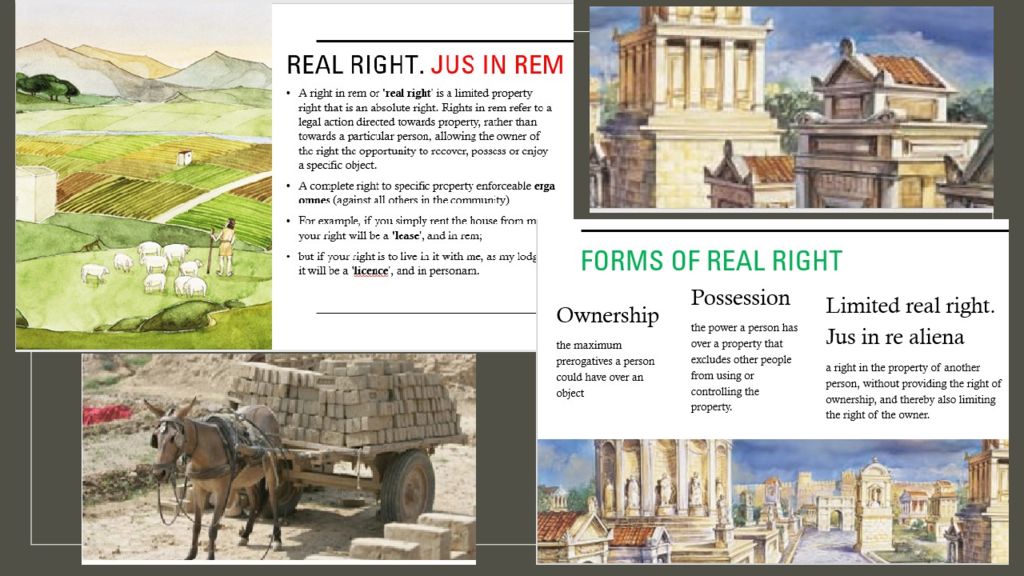

In most textbooks on Roman law, the treatment of the law of property is divided into four topics, namely the types of ‘ things ’; the different modes of acquisition and alienation of ownership of property ; ownership and possession ; and finally limited real rights in property. The Roman law of things ( ius rerum ) or, in contemporary terms, ‘ property ’, covered a much broader field than that encompassed by the modern law of property.

Слайд 18

In Ancient Rome by the end of the II century B.C. the right of private ownership of land is fully formalized. This was facilitated by the following three factors : 1) the development of agrarian legislation ; 2) the active role of praetorian law ; 3) the improvement of civil law through the activity of jurists. In principle, ownership ( dominium ex iure Quiritium ) was the most complete or extensive right a person could hold in respect of a corporeal thing. The holder of such right had the maximum prerogatives a person could have over an object: he had the right to use, enjoy and even abuse his property : ius utendi, ius fruendi, ius abutendi, as well as to alienate it, in whole or in part, as he saw fit. In short, the owner ( dominus ) could perform virtually any factual or legal act in respect of his property.

Слайд 20

During the Classical period, a new reality emerges in Roman legal practice, several forms of ownership appear at once : the Quiritian property (the most ancient and patrician form ), the Peregrine property ( property of foreigners ), Provincial property on the frontiers of the Empire and the Praetorian property ( Latin: in bonis habere ). The legal construction of the right of property assumed that the subject was only a Roman citizen or sometimes a Latin citizen who had the right of jus commercii. Such legal ownership was acquired only by legal means, and was therefore referred to as quirite ownership ( Latin : dominium ex jure Quiritium ). However, by the III – II centuries B.C. the conservatism and stability of this ancient type of Property led to the collision of legal practice with the changing socio-economic needs and the new requirements of commercial turnover. Dominium ex jure Quiritium

Слайд 21

As the most extensive of all real rights, ownership had to be acquired in a prescribed manner. Roman law knew several modes of ownership acquisition which all depended on some recognized and public assertion of control of the property. The modes of acquisition may also be classified into ‘ original ’ (or ‘natural’) and ‘ derived ’. Original modes of acquisition of ownership were those where the person acquired the right of ownership in respect of a thing without intervention by or dependence on another person. The principal modes of original acquisition of ownership were prescription (which assumed various forms ), occupatio and accessio. Derived ownership occurred where a person acquired ownership of a thing from another. T he ownership was transferred or passed from one person to another with the cooperation of the first person. The chief forms of derived acquisition of ownership were mancipatio, in iure cessio and traditio.

Слайд 22

The ownership of res nec mancipi could be transferred by traditio, the actual physical delivery of a corporeal thing on the grounds of some lawful cause ( iusta causa ). Important forms of original acquisition of ownership were : (1) occupatio and (2) accessio. Occupatio was the act of taking possession of a thing belonging to no one ( res nullius ) but capable of being in commercio with the intention of becoming owner thereof. Things that could be acquired in this way included wild animals, birds, bees and fish ; the spoils of war or booty seized from an enemy. Accessio occurred when separate things belonging to different owners were inseparably joined to each other or merged in such a manner that a new entity or object was established. A further way of acquiring ownership was specificatio, the making of a new thing out of materials belonging to another who did not consent (for example, wine from grapes, or a garment from wool ). The owner of the material should also become owner of the new object or where there were two or more owners, the latter should own the object jointly and in proportion to their contribution.

Слайд 25

When a res mancipi had been transferred to someone informally by means of mere delivery ( traditio ) rather than by means of the formal procedures of mancipatio or in iure cessio, in such a case, the transferee could not become dominus ex iure Quiritium of the property. But the praetor intervened and placed such person in the factual position of a civil law owner. The property was then regarded as in bonis and the transferee as a bonitary owner who could acquire true Roman law ownership through possession of the thing for a prescribed period by means of usucapio. The most important legal remedies an owner could employ to protect their rights were the rei vindicatio and the actio ad exhibendum, an action usually employed before an owner initiated the rei vindicatio. The purpose of the rei vindicatio was twofold : to determine ownership of the object in question and, once this had been established, to compel the defendant to return the object to its lawful owner or face being ordered to pay a sum of money.

Слайд 27

A further remedy available to the owner was the actio negatoria, or ‘ action of denial ’. This action was instituted by the owner of landed property against any person who, without challenging the plaintiff’s right of ownership, claimed a servitude or similar right in respect of his land. The aim of such action was to obtain a court order confirming that the plaintiff had full ownership not encumbered by the existence of any right of the defendant and forbidding the latter from arrogating to himself such right or calling upon him to restore the status quo.

Слайд 28

In Roman law, a servitude ( servitus ) was a real right in property belonging to another (ius in re aliena ), which restricted the rights and powers of the owner of that property. It amounted to a burden on property, to which the owner was required to submit. the four earliest of the servitude — the right to pass through another’s land ( iter ), the right to drive draft animals across land (actus), the right to use a road on one’s land for driving in a carriage or riding on horseback ( via ), and the right to draw water across land by means of an aqueduct or furrow ( aquaeductus ). Besides the rural praedial servitudes ( iura praediorum rusticorum ), a number of urban praedial servitudes ( iura praediorum urbanorum ) were also recognized. The latter were concerned with urban utilization ( regardless of whether the relevant immovable property was located in a city or the country ). Well-known servitudes of this type included the right to drive a beam into a neighbour’s building or wall ( servitus tigni immittendi ); the right to discharge rainwater through a gutter or something similar onto another’s land ( servitus fluminis recipiendi ); and the right to prevent a neighbour from obscuring one’s light ( servitus ne luminibus officiatur ).

Слайд 32

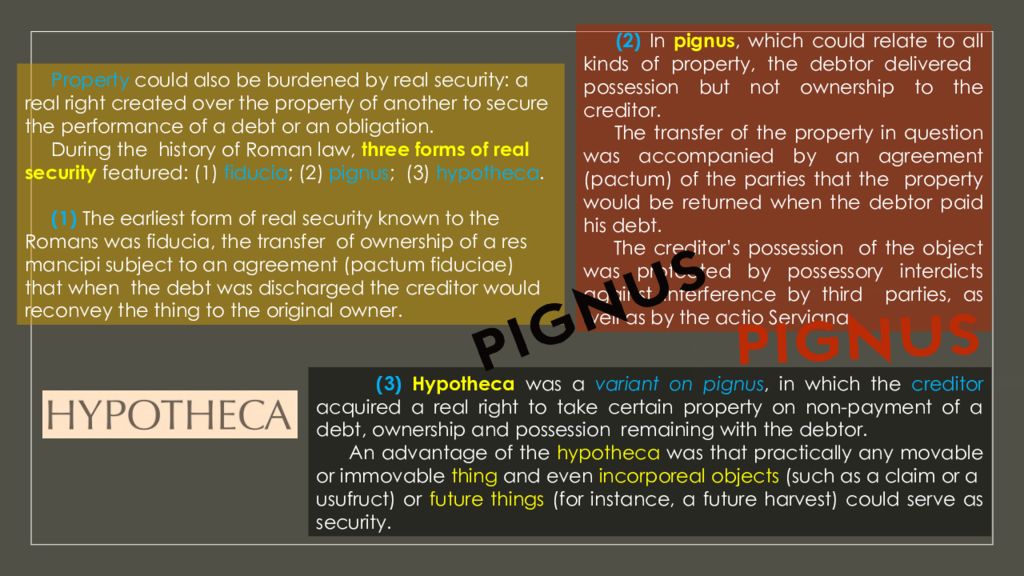

Property could also be burdened by real security: a real right created over the property of another to secure the performance of a debt or an obligation. During the history of Roman law, three forms of real security featured : (1) fiducia ; (2) pignus ; (3) hypotheca. (1) The earliest form of real security known to the Romans was fiducia, the transfer of ownership of a res mancipi subject to an agreement ( pactum fiduciae ) that when the debt was discharged the creditor would reconvey the thing to the original owner. (2) In pignus, which could relate to all kinds of property, the debtor delivered possession but not ownership to the creditor. The transfer of the property in question was accompanied by an agreement ( pactum ) of the parties that the property would be returned when the debtor paid his debt. The creditor’s possession of the object was protected by possessory interdicts against interference by third parties, as well as by the actio Serviana. (3) Hypotheca was a variant on pignus, in which the creditor acquired a real right to take certain property on non-payment of a debt, ownership and possession remaining with the debtor. An advantage of the hypotheca was that practically any movable or immovable thing and even incorporeal objects ( such as a claim or a usufruct ) or future things (for instance, a future harvest ) could serve as security.

Слайд 33

The right of private property was gradually developed in Roman jurisprudence. The main characteristic of it was not at all unrestrictedness, since restrictions on the right of ownership were nevertheless enshrined in Roman law (for example, by means of servitudes ). The main thing for the right of ownership was : First, the existence of a legal basis ( titulus ) acquired by strictly established civil means; Secondly, the existence of dominion over a thing “ in full right ” ; Thirdly, the possession of special legal means of protection of this right and the means of free realization of these means.