Слайд 3

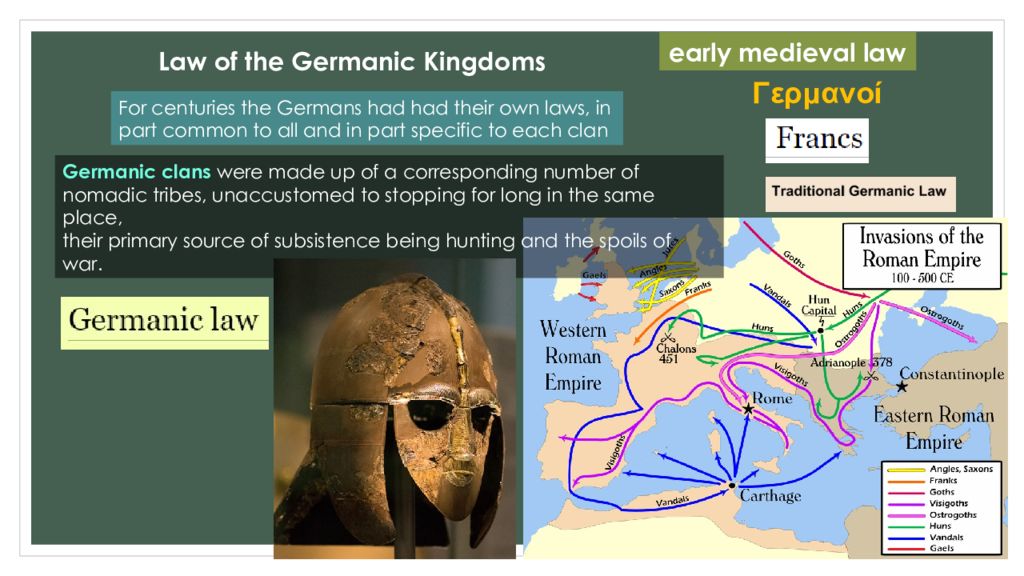

Law of the Germanic Kingdoms For centuries the Germans had had their own laws, in part common to all and in part specific to each clan Germanic clans were made up of a corresponding number of nomadic tribes, unaccustomed to stopping for long in the same place, their primary source of subsistence being hunting and the spoils of war. Γερμανοί early medieval law

Слайд 4

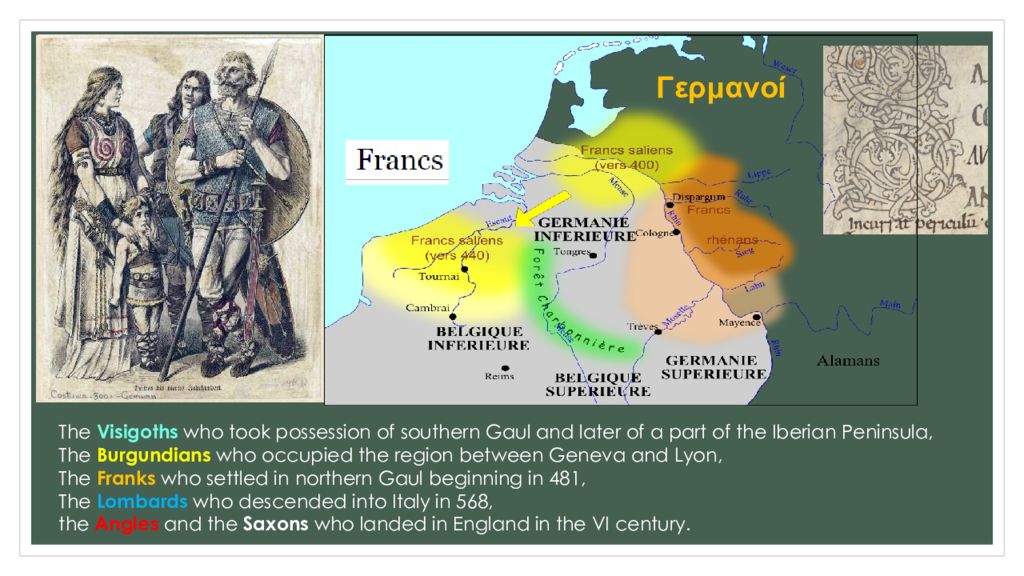

The Visigoths who took possession of southern Gaul and later of a part of the Iberian Peninsula, The Burgundians who occupied the region between Geneva and Lyon, The Franks who settled in northern Gaul beginning in 481, The Lombards who descended into Italy in 568, the Angles and the Saxons who landed in England in the VI century. Γερμανοί

Слайд 5

The Germanic tribes, having thus become masters of vast territories, found themselves governing a population who until then had been living under Roman law, whereas the victors practised completely different customs, It posed the problem of how to retain the legal traditions to which each of the Germanic races was so strongly tied, and which for centuries had symbolised their identity and the values they shared. The legitimate existence was recognised within single Germanic kingdoms of a plurality of laws, each of which was applicable to a specific ethnicity. It was the beginning of the personality of the law – a fundamental feature in this historical phase. This was also possible because the juridical relationships between the ethnicities – in the first place between the victors and the vanquished were for a time almost non- existent : mixed marriages, contracts, trade agreements etc. Γερμανοί

Слайд 6

In order to ensure a sufficiently uniform hold on Germanic customs, though in different times and in different ways, each of the new Germanic kingdoms came to possess written legal texts, -- in which the national Germanic traditions were variously explicated and supplemented with new elements, in part drawn from the law of the vanquished – Roman law, in part from the one newly established by the sovereigns. These laws almost always adopted the Latin language, even when their content was intended to have a strictly Germanic stamp. Γερμανοί While the Leges Barbarorum were written in Latin and not in any Germanic vernacular, codes of Anglo- Saxon law were produced in Old English. early medieval law

Слайд 7

Γερμανοί Germanic law is a scholarly term used to described a series of commonalities between the various law codes of the early Germanic peoples – the Leges Barbarorum, « laws of the barbarians », also called Leges. This law was seen as an essential element in the formation of modern European law and identity, alongside the Roman law and canon law. The Leges Barbarorum were all written under Roman and Christian influence and often with the help of Roman jurists. A dditionally, the Leges contain large amounts of " Vulgar Latin law ", an unofficial legal system that functioned in the Roman provinces. early medieval law

Слайд 8

The tripartite social order of the Middle Ages : Oratores ("those who pray"), Bellatores ("those who fight"), Laboratores ("those who work"). The Germanic " modes of thought " ( Denkformen ) still existed, with important elements being an emphasis on orality, gesture, formulaic language, legal symbolism, and ritual. The early medieval law shows many features that might be called Germanic " new archaic ". Some items in the Leges, such as the use of vernacular words, may reveal aspects of originally Germanic, or at least non-Roman, law. This vernacular, often in the form of Latinized words, shows some similarities to Gothic. early medieval law Γερμανοί

Слайд 9

A word attested meaning " law " in West Germanic languages is represented by Old High German êwa. This word Êwa is used in the Latin texts of the Leges barbaroum to mean the unwritten laws and customs of the people, but comes also to refer to the codified written laws as well. Γερμανοί

Слайд 10

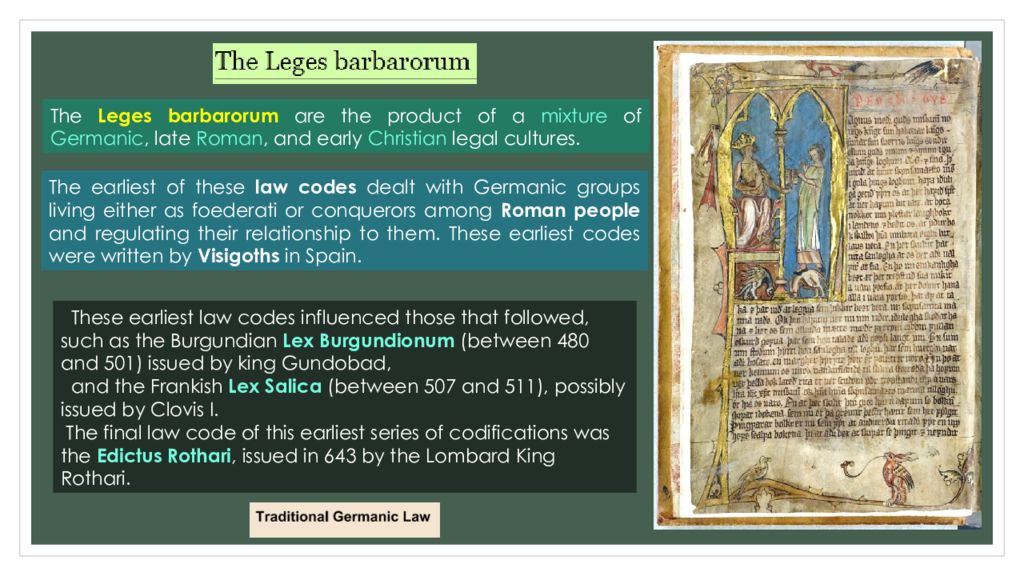

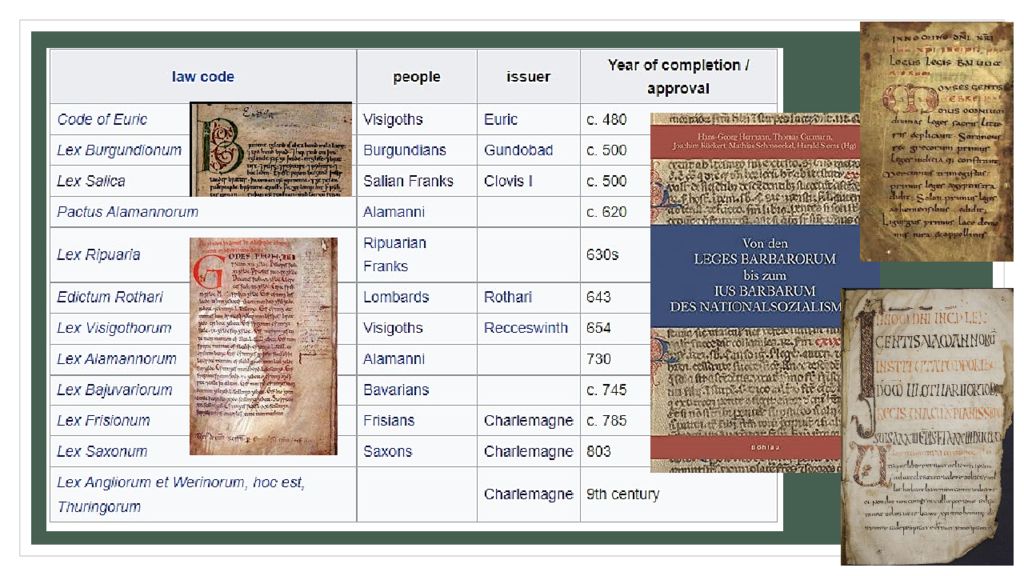

The Leges barbarorum are the product of a mixture of Germanic, late Roman, and early Christian legal cultures. The earliest of these law codes dealt with Germanic groups living either as foederati or conquerors among Roman people and regulating their relationship to them. These earliest codes were written by Visigoths in Spain. These earliest law codes influenced those that followed, such as the Burgundian Lex Burgundionum ( between 480 and 501) issued by king Gundobad, and the Frankish Lex Salica ( between 507 and 511), possibly issued by Clovis I. The final law code of this earliest series of codifications was the Edictus Rothari, issued in 643 by the Lombard King Rothari.

Слайд 12

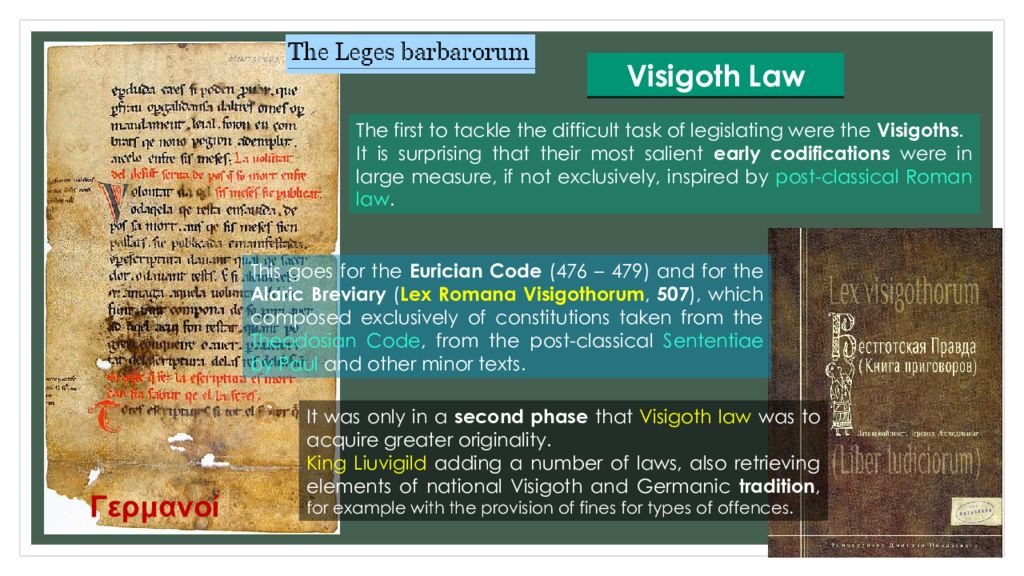

Visigoth Law The first to tackle the difficult task of legislating were the Visigoths. It is surprising that their most salient early codifications were in large measure, if not exclusively, inspired by post-classical Roman law. This goes for the Eurician Code (476 – 479) and for the Alaric Breviary ( Lex Romana Visigothorum, 507 ), which composed exclusively of constitutions taken from the Theodosian Code, from the post-classical Sententiae by Paul and other minor texts. It was only in a second phase that Visigoth law was to acquire greater originality. King Liuvigild adding a number of laws, also retrieving elements of national Visigoth and Germanic tradition, for example with the provision of fines for types of offences. Γερμανοί

Слайд 13

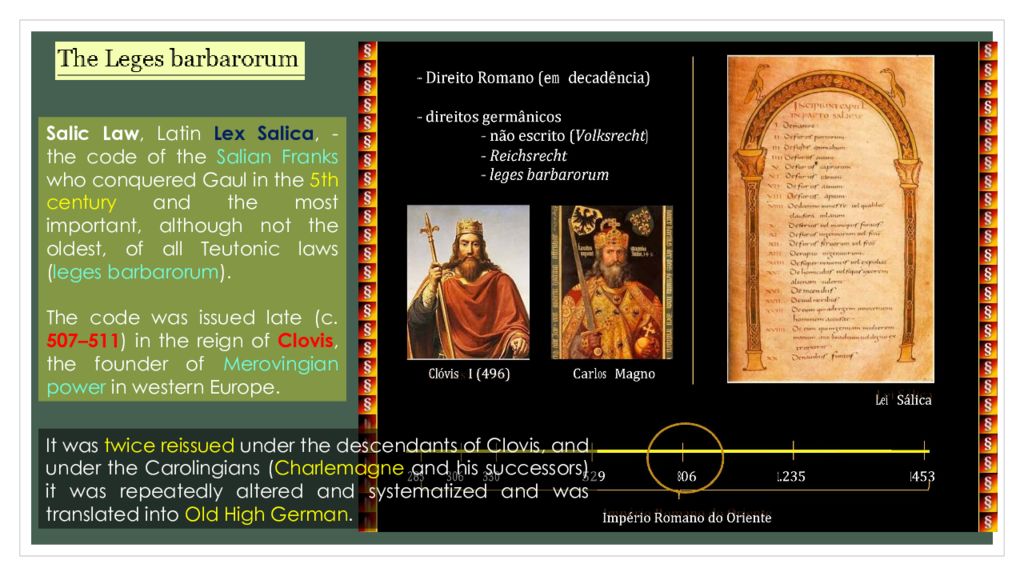

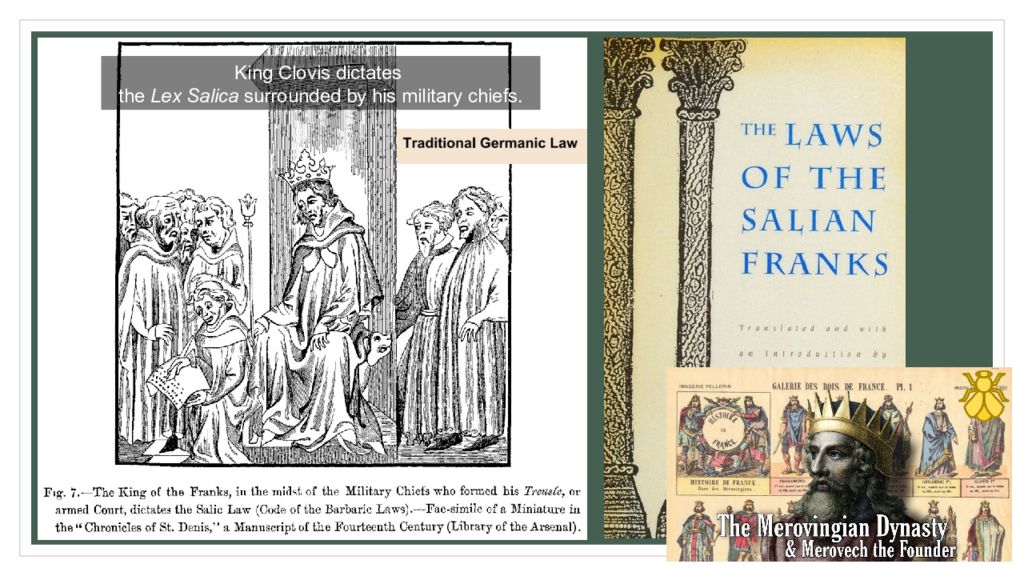

Salic Law, Latin Lex Salica, - the code of the Salian Franks who conquered Gaul in the 5th century and the most important, although not the oldest, of all Teutonic laws ( leges barbarorum ). The code was issued late (c. 507–511 ) in the reign of Clovis, the founder of Merovingian power in western Europe. It was twice reissued under the descendants of Clovis, and under the Carolingians ( Charlemagne and his successors ) it was repeatedly altered and systematized and was translated into Old High German.

Слайд 15

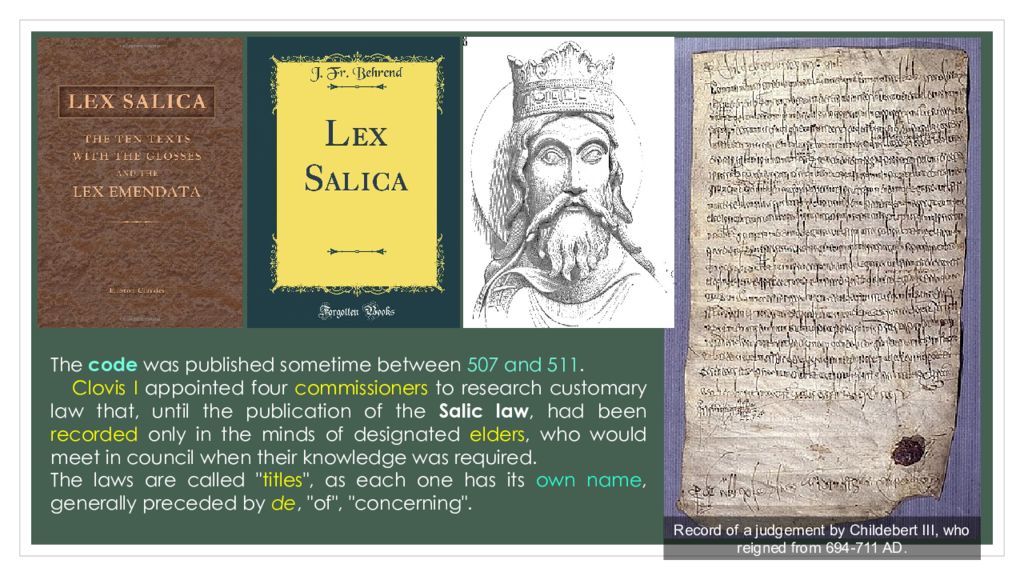

Record of a judgement by Childebert III, who reigned from 694-711 AD. The code was published sometime between 507 and 511. Clovis I appointed four commissioners to research customary law that, until the publication of the Salic law, had been recorded only in the minds of designated elders, who would meet in council when their knowledge was required. The laws are called " titles ", as each one has its own name, generally preceded by de, "of", "concerning".

Слайд 16

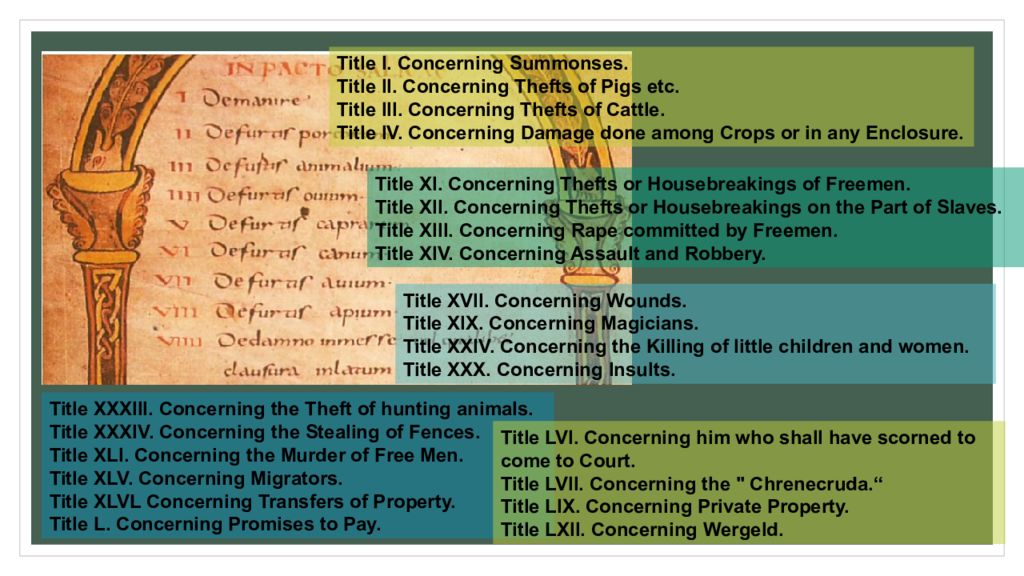

Title I. Concerning Summonses. Title II. Concerning Thefts of Pigs etc. Title III. Concerning Thefts of Cattle. Title IV. Concerning Damage done among Crops or in any Enclosure. Title XI. Concerning Thefts or Housebreakings of Freemen. Title XII. Concerning Thefts or Housebreakings on the Part of Slaves. Title XIII. Concerning Rape committed by Freemen. Title XIV. Concerning Assault and Robbery. Title XVII. Concerning Wounds. Title XIX. Concerning Magicians. Title XXIV. Concerning the Killing of little children and women. Title XXX. Concerning Insults. Title XXXIII. Concerning the Theft of hunting animals. Title XXXIV. Concerning the Stealing of Fences. Title XLI. Concerning the Murder of Free Men. Title XLV. Concerning Migrators. Title XLVL Concerning Transfers of Property. Title L. Concerning Promises to Pay. Title LVI. Concerning him who shall have scorned to come to Court. Title LVII. Concerning the " Chrenecruda.“ Title LIX. Concerning Private Property. Title LXII. Concerning Wergeld.

Слайд 17

The Salic Law concerns itself with the most manifold branches of administration. The system of landholding, the nature of the early village community, the relations of the Germans to the Romans, the position of the king, the classes of the population, family life, the disposal of property, judicial procedure, the ethical views, are all illustrated in its sixty-five articles. How clearly does the Title on insults show the regard paid for personal bravery and for female chastity ! The false charge of having thrown away one's shield was punished as severely as assault and battery. T he person who groundlessly called a woman unclean paid a fine, second only in severity to that imposed for attempted murder ! Pactus Legis Salicae

Слайд 18

The Salic Law is primarily a penal and procedural code, containing a long list of fines ( compositio ) for various offenses and crimes. It also includes, however, some civil-law enactments, among these a chapter that declares that daughters cannot inherit land. * Although this section of the Lex Sdalica was not invoked in the exclusion of the daughters of Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV from the throne, but (!) it took on critical importance under the later Valois (16th century), when it was incorrectly cited as authority for the existing assumption that women should not succeed to the crown. Despite the fact that it was first written down in Latin ( after a long period of purely oral transmission ), the Salic Law was very little influenced by Roman law.

Слайд 19

Marriage in t he Salic Law The historians divided Germanic marriages into 3 types : 1) Muntehe, characterized by a marriage treaty, the granting of a bride gift or morning gift to the bride, and the acquisition of munt, or legal power, of the husband over the wife ; 2) Friedelehe, (from Old High German : friudila, Old Norse : friðla, frilla " beloved "), a form of marriage lacking a bride or morning gift and in which the husband did not have munt over his wife (this remained with her family ); 3 ) Kebsehe ( concubinage ), the marriage of a free man to an unfree woman.

Слайд 20

The law uses capital punishment only in cases of witchcraft and poisoning. This absence of violence is a unique feature of the Salic Law. The use of fines as the main reparation made it so that those with the money to pay the fine had the ability to get away with the most heinous of crimes. " Those who commit rape shall be compelled to pay 2500 denars, which makes 63 shillings." All crimes committed against Romans had lesser fines than other social classes.

Слайд 21

The fines in Lex Salica placed different values on the gender and ethnic demographics. This social capital is evident in the differences in the Salic Law's punishment for murder based on a woman's ability to bear children. Women who could bear children were protected by a 600 shilling fine while the fine for murdering a woman who could no longer bear children was only 200 shillings.

Слайд 22

The Salic Law outlines a unique way of securing the payment of money owed. It is called the Chrenecruda. In cases where the debtor could not pay back a loan in full they were forced to clear out everything from their home. If the debt still could not be paid off the owner could collect dust from all four corners of the house and cross the threshold. The debtor then turned and face the house with their next of kin gathered behind them. The debtor threw the dust over their shoulder. The person (or persons ) that the dust fell upon was then responsible for the payment of the debt. The process continued through the family until the debt was paid. Chrenecruda helped secure loans within the Frankish society. It intertwined the loosely gathered tribes and helped to establish government authority. The process made a single person part of a whole group. Title LVII. Concerning the " Chrenecruda “ Pactus Legis Salicae

Слайд 23

Pactus Legis Salicae The purpose was that of substituting the original reprisal or faida with the legal compositio, imposed in monetary terms. Salic law presupposed an economy still predominantly based on a nomadic way of life (there is very little on the possession of landed property and no rules on the illicit occupation of land ) k Lex Salica with particular attention paid to questions tied to domestic animals, as attested to by the m e ticulousn e ss of the rulings to do with as many as five breeds of pigs. In case of homicide the pecuniary fines are differentiated according to whether the act of killing was manifest or covert, whether the victim was a man or a woman, a soldier of war or a civilian, a follower of the king, a Frank or a Roman, the landowner or a peasant.

Слайд 24

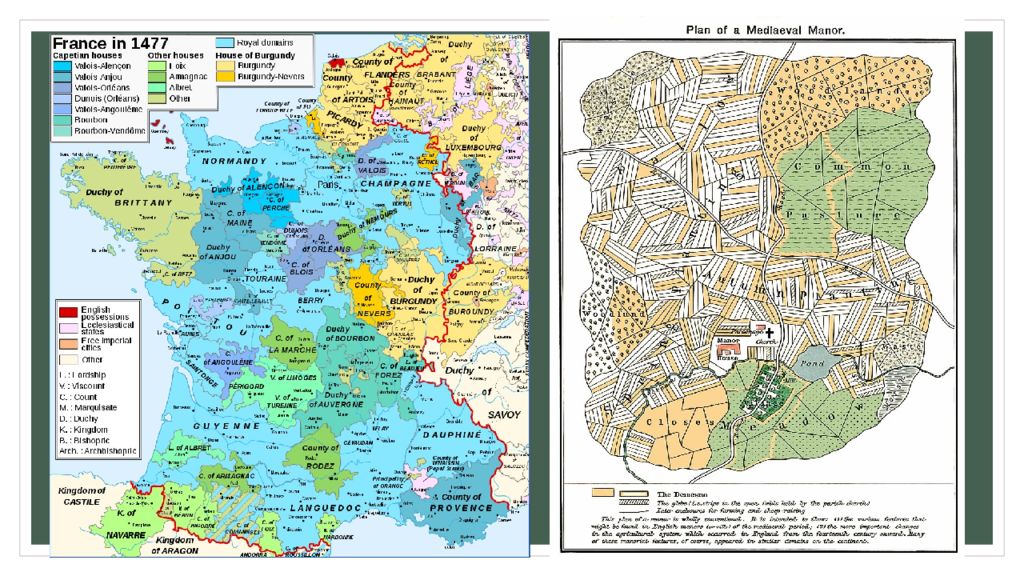

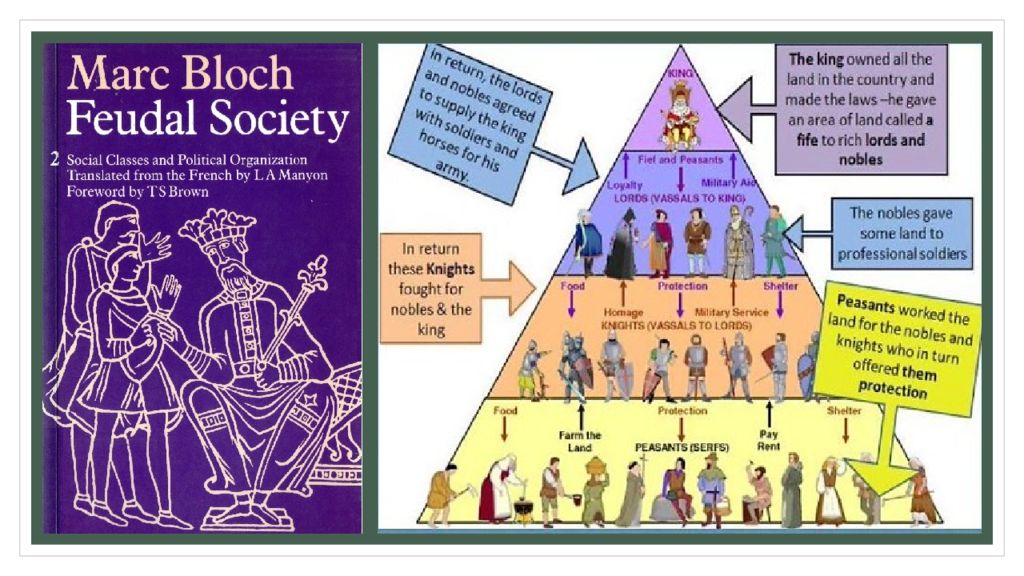

The Classical Medieval Law in Feudal Age In the Middle Ages (5th - 17th centuries ), the main elements of common European legal culture arose, special outlines of two world legal families were formed – continental European and Anglo-American law, and specific features of national legal systems were laid down. In the historical and legal literature, a number of characteristic features of the medieval legal culture that developed during the heyday of the feudal legal order in European countries are distinguished : I. The dominant place in the medieval system of feudal law was occupied by the norms that regulated personal and land relations between the feudal lord s themselves ( land owners ) and the feudal & peasants ( land holders ), the domain ( manorial ) law.

Слайд 26

II. Feudal law was characterized as the right of the strong, " fist law" with its cult of brute force in resolving personal and social conflicts, for example, in relation to a feudal dependent peasant or in relations with a neighboring feudal lord ( private wars, feudal civil strife, knightly duels, "judicial field "). III. The class principle of the feudal law explains that there was no division into modern branches of law in it, i.e. a set of norms for regulating a certain sphere of the objective activity of society, but there was a division into a number of estate legal subsystems : fief (fief) law, domain (manorial) law, church (canonical) law, city (communal) law, Roman (reception) law, etc.

Слайд 27

IV. The class division of the feudal population into higher and lower categories ( estates ), the hierarchical structure of society left its mark on the legal institutions of feudal law, determined its pronounced class character. Therefore, the right of the medieval period was a “ right-privilege ” (lat. privilegium, from privius - “special, single”, and lex - “law”), which assumed the granting by the royal power of certain privileges, liberties and preferences ( beneficia juris ) to certain social estates, ethno-confessional groups, free cities, monasteries or lands. In particular, the principle of the exclusivity of the legal status ( jus speciale ) of those persons who belonged to the upper rungs of the feudal ladder, and the principle of the “ court of peers ”, created for each class as a court of equals, were in effect.

Слайд 28

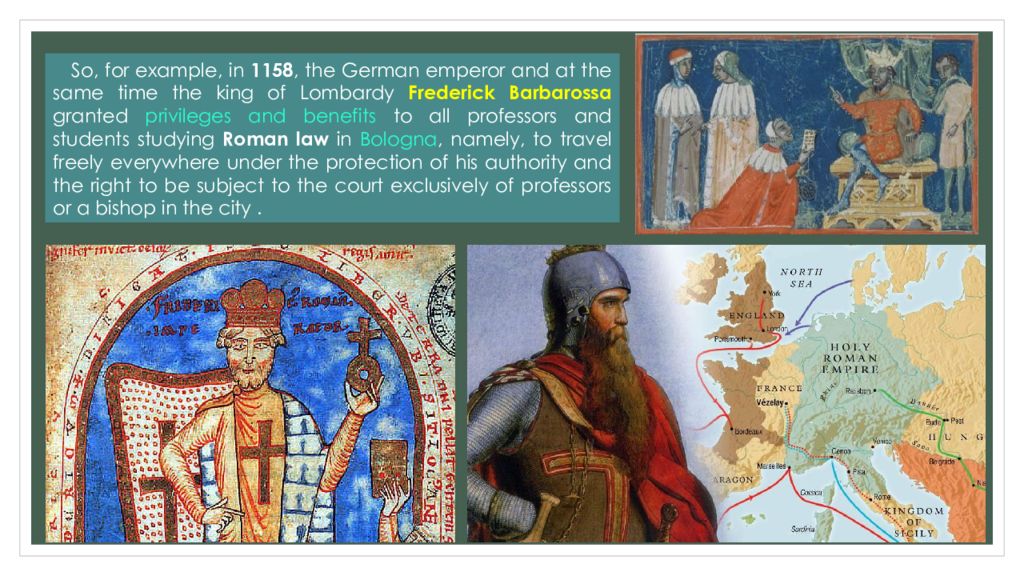

So, for example, in 1158, the German emperor and at the same time the king of Lombardy Frederick Barbarossa granted privileges and benefits to all professors and students studying Roman law in Bologna, namely, to travel freely everywhere under the protection of his authority and the right to be subject to the court exclusively of professors or a bishop in the city.

Слайд 29

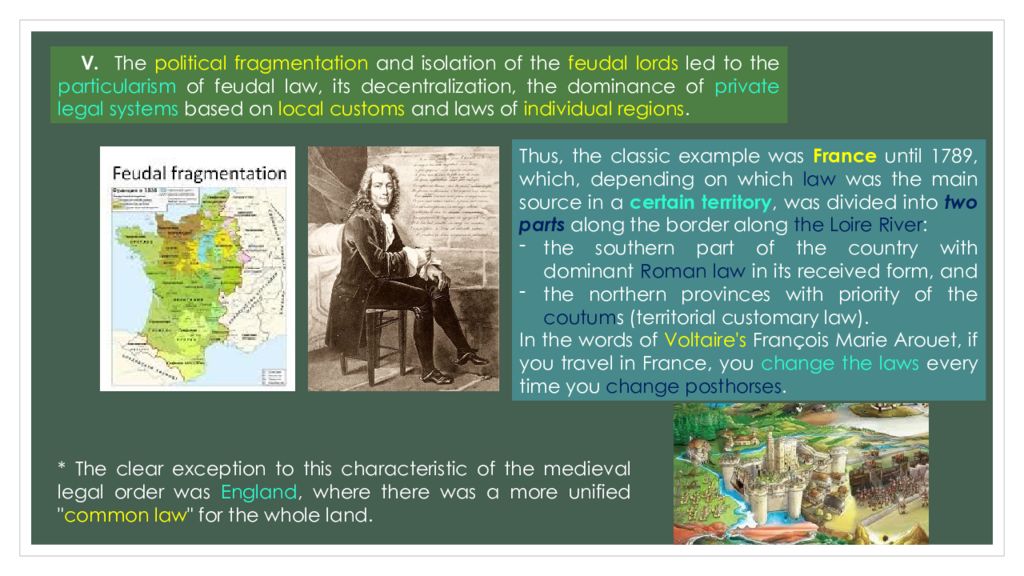

V. The political fragmentation and isolation of the feudal lords led to the particularism of feudal law, its decentralization, the dominance of private legal systems based on local customs and laws of individual regions. Thus, the classic example was France until 1789, which, depending on which law was the main source in a certain territory, was divided into two parts along the border along the Loire River : the southern part of the country with dominant Roman law in its received form, and the northern provinces with priority of the coutum s ( territorial customary law ). In the words of Voltaire's François Marie Arouet, if you travel in France, you change the laws every time you change posthorses. * The clear exception to this characteristic of the medieval legal order was England, where there was a more unified " common law " for the whole land.

Слайд 31

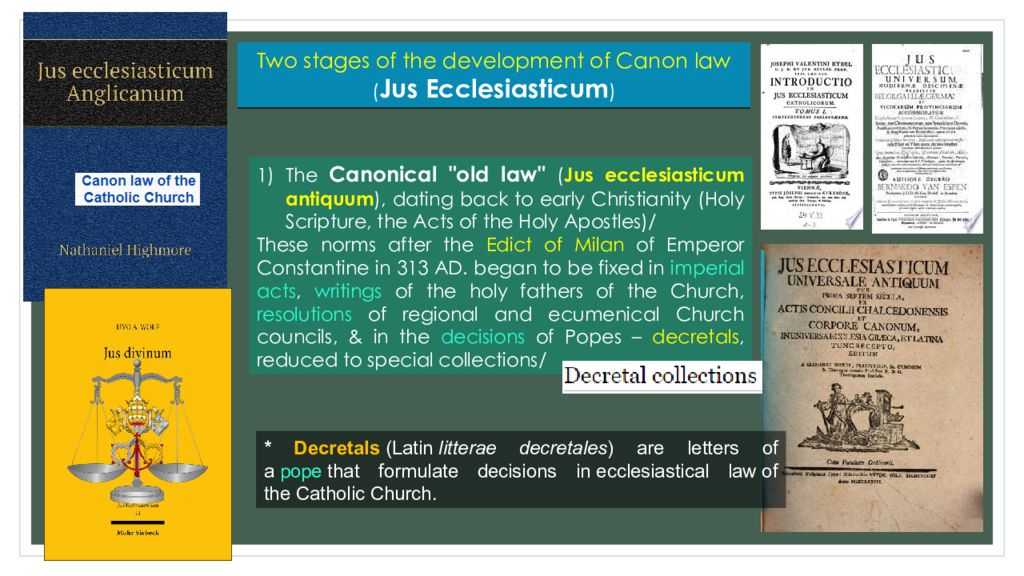

VI. The great and determining influence of religious norms on feudal legal norms, mixing them with secular jurisprudence. Canon law refers to the body of rules and regulations governing the Christian Church and its members. Medieval canon law developed & regulated the intra-church order and relations between members of the secular community: family and inheritance, contracts, punishment for religious crimes. In the history of the development of Medieval canon law (jus ecclesiasticum), two stages can be distinguished :

Слайд 32

Two stages of the development of Canon law ( Jus Ecclesiasticum ) The Canonical " old law" ( Jus ecclesiasticum antiquum ), dating back to early Christianity ( Holy Scripture, the Acts of the Holy Apostles ) / These norms after the Edict of Milan of Emperor Constantine in 313 AD. began to be fixed in imperial acts, writings of the holy fathers of the C hurch, resolutions of regional and ecumenical C hurch councils, & in the decisions of Popes – decretals, reduced to special collections / * Decretals ( Latin litterae decretales ) are letters of a pope that formulate decisions in ecclesiastical law of the Catholic Church.

Слайд 33

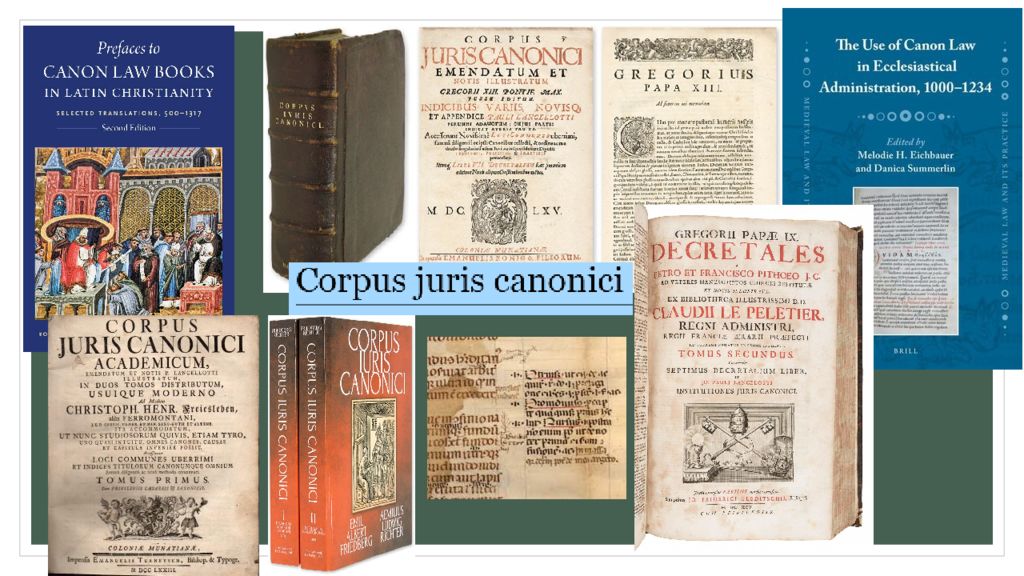

2 ) The Canonical “new law” ( jus canonicum novum ), the main sources of which were the papal constitutions (bulls, breves, encyclicals, rescripts), and the “Decree of Gratian” of 1140, where approx. 3800 canonical texts. Then in 1500, under Pope Boniface VIII, the Extravagantae appeared, becoming a collection of decretals beginning with Pope Clement V in 1317, which later received the official name of the Corpus Juris Canonici at the end of the 16th century.

Слайд 35

VII. With the development of commodity-money relations in a feudal society and the growth of free cities, a need arose for some ready-made, carefully developed legal recipes for regulating trade turnover and formalizing commercial transactions based on the idea of formal equality and independence of participants in trade. As a result, there is an increased interest in Roman private law and the process of its reception begins (from the Latin receptio - borrowing, assimilation, processing, restoration of action ), its Renaissance with the subsequent adaptation of legal definitions, concepts, law structures and institutions to new socio-economic, political and cultural realities of the Middle Ages.

Слайд 36

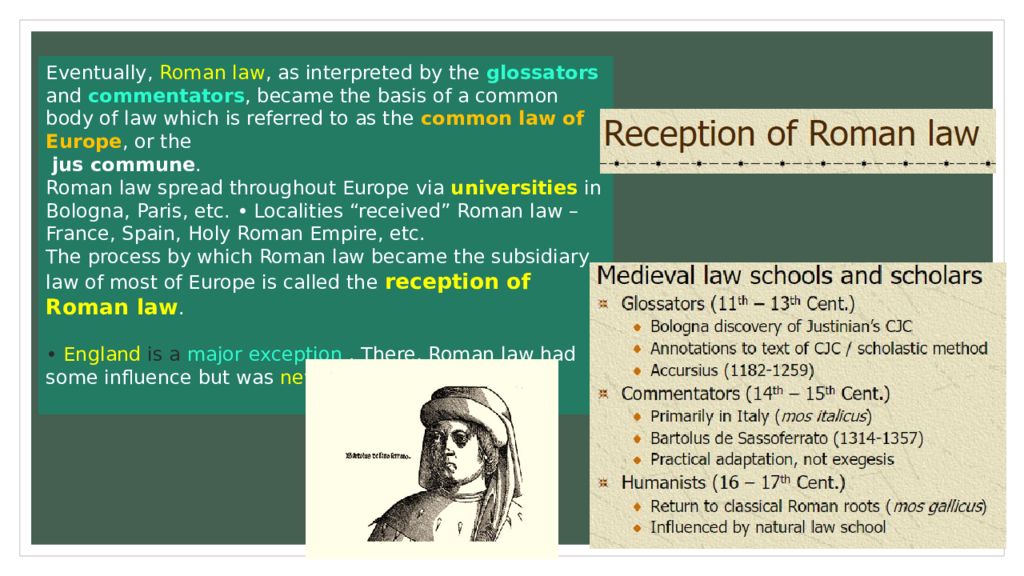

Eventually, Roman law, as interpreted by the glossators and commentators, became the basis of a common body of law which is referred to as the common law of Europe, or the jus commune. Roman law spread throughout Europe via universities in Bologna, Paris, etc. • Localities “received” Roman law – France, Spain, Holy Roman Empire, etc. The process by which Roman law became the subsidiary law of most of Europe is called the reception of Roman law. • England is a major exception . There, Roman law had some influence but was never accepted.

Слайд 37

In historical and legal literature, much attention is paid to the causes and origins of reception, its national forms and significance in the history of Western law, to the stages of development of individual schools of reception and the place of received law in national jurisdictions. So, c onsider further the stages of development of Roman law in the Medieval culture. 1. Direct application of Roman law in the barbarian kingdoms. Already at the end of the 5th - 6th centuries Roman law, which continued its life after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, although it ceased to be that same classical law, was woven into a historical synthesis with the customary law of the ancient Germanic tribes who founded their kingdoms on the ruins of the old Empire. Gradually, it turned from a law for the Spanish and Gallo -Roman population into a common law for all the resettled Germanic peoples, was recorded in their tribal collections in " vulgar " Latin and became more simplified & barbarized.

Слайд 38

In particular, Roman legal provisions were directly enshrined in the Edict of Theodoric I, the Ostrogothic king ( Edictum Theoderici, or Lex Romana Ostrogothorum), which was in force from 500 to 550, as well as in the Breviary of Alaric II, the Visigothic king of 506 ( Breviarium Alarici, or Lex Romana Visigothorum). Transforming into a kind of Romance -Germanic law, vulgarized Roman law was used in its own German collections of laws and in the so-called Barbarian Leges. In the early medieval kingdoms, both private codifications of Roman law (the writings of the jurists Paul, Ulpian, Gaius, and others, the codes of Gregorian and Hermogenian ) were directly borrowed, as well as the official “ Code of Theodosius ” ( lat. Codex Theodosianus) of 438, in its simplified version as one of the first sets of imperial constitutions common in Europe before the codification of Justinian.

Слайд 39

Soon the direct application of Roman law led to its falling into disuse, being absorbed into royal legislation. Thus, in early medieval England, Roman legal traditions were almost completely lost. But in continental Europe, such a community of scientists (from jurists, teachers of church schools, etc.) and a practical environment ( including notaries and judicial lawyers ) developed that together contributed to the restoration of Roman traditions in European medieval law. The reception of Roman law takes its first steps in the most socially and culturally developed urban centers of northern Italy and southern France, where in the 11th-12th centuries. the first schools of theoretical and practical jurisprudence arise. It was in the cities that there was the most favorable soil for this, because the emerging bourgeoisie – the burghers saw in Roman law a ready-made tool for regulating trade transactions and strengthening private property relations, free from feudal restrictions.

Слайд 40

But t he position of representatives of the feudal estates on this issue was ambiguous. And although t he reception of certain norms of Roman law was carried out at the direction of the Roman popes, emperors and local princes, but more and more often they showed open rejection of this process. Thus, in the troubled times of the investiture conflict, the cities of Italy found in the Corpus Juris Civilis of the late Emperor Justinian an objective legal basis for the reliable regulation of their rapidly changing relations and were able, with the help of their lawyers at the universities, to derive from this tradition a new form of self-government – a commune combined with a consulate.

Слайд 41

Recognizing canon law as the bridge across which Roman legal culture passed into the feudal world, it must be taken into account that by the XIII th century papal bulls began to prohibit the teaching of Roman law, seeing it as a competitor to canon law. Subsequently, the single combat between the two legal systems ended in the defeat of church lawyers. This was largely facilitated by the feudal state itself, which was impressed by public Roman law with its idea of strong state power, recognition of the highest legal force behind imperial acts and the authority of the princeps ( like the maxim of the Roman lawyer Ulpian " Princeps legibus solutus est" ("The ruler is not bound by laws " ). In the struggle against the Roman popes and the emancipated feudal nobility, the medieval sovereigns rendered every possible assistance to the cause of the reception of Roman law.

Слайд 42

In addition to these socio-economic and political prerequisites, there were also ideological and purely legal reasons for the reception of R.L. Thus, the formal basis of reception was seen in the idea of the succession of power of the German rulers from the Roman emperors, in various ideological currents of the Renaissance and Humanism, in theological teachings, in the cult of reason common to the naturalist school of law, and also in the doctrine of the national spirit of the historical school of law. As for the legal reasons for reception, this is, firstly, the high level of development of many Roman legal institutions, the clarity of the norms of classical law, its universal, and not narrowly national, character. Secondly, the use of modified Roman law was simpler and more economical in terms of effort compared to the slowly developing local customary law, its archaism, particularism, inconsistency, etc.

Слайд 43

This renewed interest in Roman law was due to a need for a new legal system that could fulfil the needs of a developing Western European society. There was cultural and economic prosperity in Italy at the end of the 11th century and it later spread to the rest of Western Europe. There was a need for a legal system that could fulfil the needs of a more complex and sophisticated society. There was also legal diversity which came about as a result of the feudal system in Western Europe from the 9th century AD when each region, city or town had its own separate legal system. The legal diversity had a detrimental effect on trade and created a need for one universal, written legal system. So it is not surprising that jurists turned to Roman as it was a sophisticated legal system, known to everybody, easily available in the Corpus Iuris Civilis and obviously able to meet the needs of the people. The revival of Roman law was in the form of a scientific study of the Corpus Iuris Civilis by certain groups of jurists.

Слайд 44

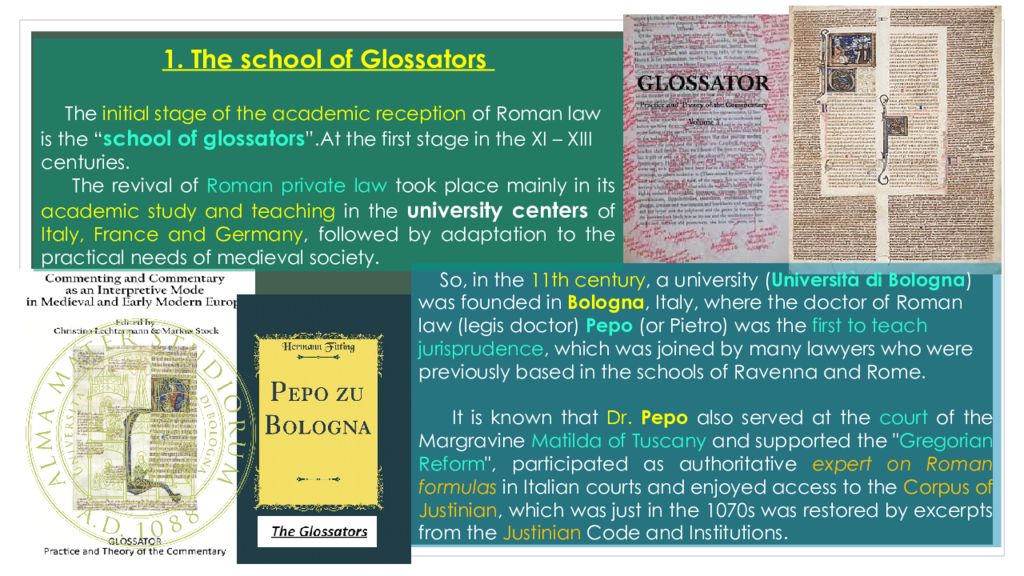

So, in the 11th century, a university ( Università di Bologna ) was founded in Bologna, Italy, where the doctor of Roman law (legis doctor) Pepo (or Pietro) was the first to teach jurisprudence, which was joined by many lawyers who were previously based in the schools of Ravenna and Rome. It is known that Dr. Pepo also served at the court of the Margravine Matilda of Tuscany and supported the " Gregorian Reform ", participated as authoritative expert on Roman formulas in Italian courts and enjoyed access to the Co rpus of Justinian, which was just in the 1070s was restored by excerpts from the Justinian Code and Institutions. 1. The school of Glossators The initial stage of the academic reception of Roman law is the “ school of glossators ”.At the first stage in the XI – XIII centuries. The revival of Roman private law took place mainly in its academic study and teaching in the university centers of Italy, France and Germany, followed by adaptation to the practical needs of medieval society.

Слайд 45

Prominent European law centers included : Bologna ( founded in 1088), Salamanca (1218), Paris (1219), Padua (1222), Naples (1224), Toulouse (1229), Oxford ( about 1240), Orleans ( about 1260), Coimbra (1290), Cambridge (1318), Prague (1348), Krakow (1364), Vienna (1365), Heidelberg (1385), among others. In the High Middle Ages, the study of Roman law was accounted a component of the study of rhetoric which, together with the two other liberal arts - dialectics und grammar ( forming the Trivium ), was cultivated especially in Rome and Ravenna.

Слайд 46

The University of Pavia, however, was the first to use the method of glosses ( brief notations of the meaning of a word ) to explain the law. This method was imported to Bologna to analyze and study the civil law, that is, the Roman law of Justinian’s Corpus Iuris. Bologna became the first academic center specifically focused on the study of Roman law, and by the end of the XII th century the Bologna School of Law held a preeminent position. Thousands of students from around Europe attended lectures there, participated in legal discussions, and received a rigorous education based on the special legal techniques developed at the law school. Law students learned a legal method, a legal grammar, rather than the specific laws to be applied in concrete cases.

Слайд 47

The name " Corpus Juris Civilis " ("Body of Civil Law") occurs for the first time in 1583 as the title of a complete edition of the Justinianic code by Dionysius Godofredus. This is the modern name for a collection of fundamental works in jurisprudence, issued from 529 to 534 by order of Justinian I, Byzantine Emperor. In Italy, from the late 11th century, there started to reappear in certain legal works and documents precise references to the Justinianic codification. Thus, for instance, in the " Judgment of Marturi " ( 1076 ) there appears for the first time a quotation from the Digest. A large number of passages from the Digest and Institutes are also to be found in the Collectio Britannica (c. 1090 ), a collection of decretals which also partly draws on the Justinianic codification.

Слайд 48

The flourishing of the science of law in Bologna in the 11th century is directly related to the exceptional event of the reappearance of the Florentine manuscript «Digest of Justinian ». This MS, whose origin is unknown, was preserved in Pisa around the year 1050, and found its way to Florence in the early 15th century as booty of war. The text of the Vulgate of the Digest occasionally diverges from the Florentina and is also incomplete in some places. I n accordance with a medieval tradition, the Vulgate of the Digest is sub-divided into three parts : the Digestum Vetus (books 1–24.2), the Digestum Novum (books 39–50) ; the Digestum Infortiatum (books 24.3–38). From the law studies there gradually developed a standard edition of the Digest – the Vulgata or Littera Bononiensis, which formed the basis of legal instruction. As later textual criticism has shown, all versions of the Vulgata derived directly or indirectly – from one sole MS, the Littera Florentina or Pisana.

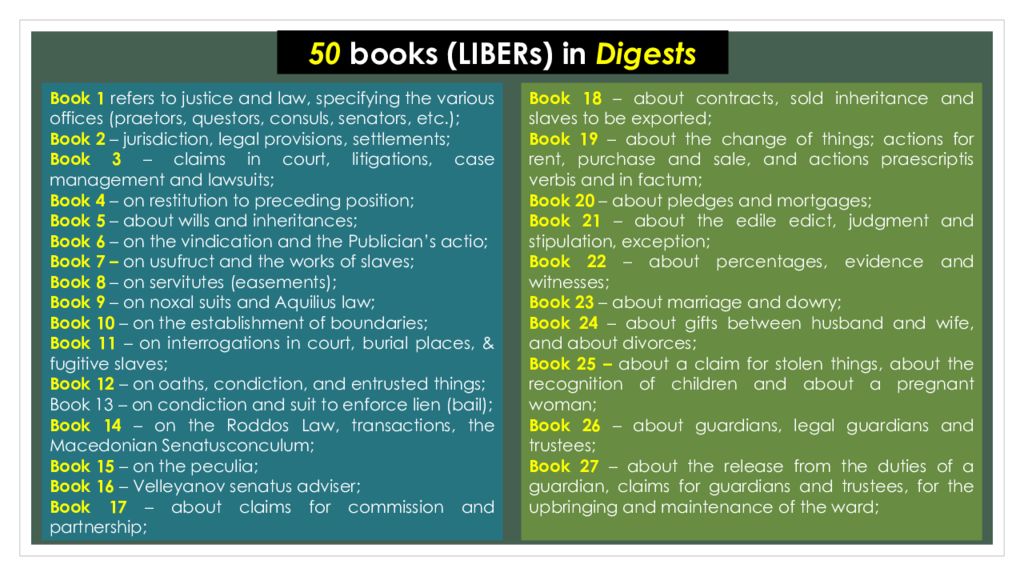

Слайд 49

Book 1 refers to justice and law, specifying the various offices ( praetors, questors, consuls, senators, etc.); Book 2 – jurisdiction, legal provisions, settlements ; Book 3 – claims in court, litigations, case management and lawsuits ; Book 4 – on restitution to preceding position; Book 5 – about wills and inheritances ; Book 6 – on the vindication and the Public i an ’s actio ; Book 7 – on usufruct and the works of slaves ; Book 8 – on servitutes ( easements ) ; Book 9 – on noxal suits and Aquilius law; Book 10 – on the establishment of boundaries ; Book 11 – on interrogations in court, burial places, & fugitive slaves ; Book 12 – on oaths, condiction, and entrusted things ; Book 13 – on condiction and suit to enforce lien ( bail) ; Book 14 – on the Roddos Law, transactions, the Macedonian Senatusconculum ; Book 1 5 – on the peculia ; Book 16 – Velleyanov senatus adviser ; Book 17 – about claims for commission and partnership ; 50 books ( LIBERs) in Digests Book 18 – about contracts, sold inheritance and slaves to be exported ; B ook 19 – about the change of things ; actions for rent, purchase and sale, and actions praescriptis verbis and in factum ; Book 20 – about pledges and mortgages ; Book 21 – about the edile edict, judgment and stipulation, exception ; B ook 22 – about percentages, evidence and witnesses ; B ook 2 3 – about marriage and dowry ; B ook 2 4 – about gifts between husband and wife, and about divorces ; B ook 2 5 – about a claim for stolen things, about the recognition of children and about a pregnant woman; B ook 2 6 – about guardians, legal guardians and trustees ; B ook 2 7 – about the release from the duties of a guardian, claims for guardians and trustees, for the upbringing and maintenance of the ward ;

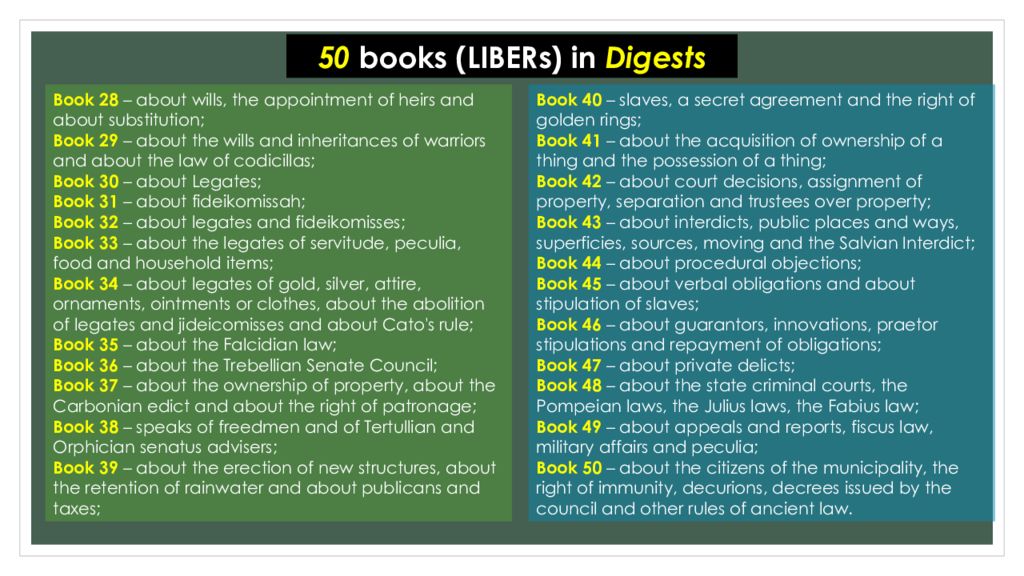

Слайд 50

50 books ( LIBERs) in Digests Book 28 – about wills, the appointment of heirs and about substitution; Book 2 9 – about the wills and inheritances of warriors and about the law of codicillas ; Book 30 – about Legates; Book 31 – about fideikomissah ; Book 3 2 – about legates and fideikomisses ; Book 33 – about the legates of servitude, peculia, food and household items; Book 34 – about legates of gold, silver, attire, ornaments, ointments or clothes, about the abolition of legates and jideicomisses and about Cato's rule; Book 35 – about the Falcidian law; Book 36 – about the Trebellian Senate Council; Book 37 – about the ownership of property, about the Carbonian edict and about the right of patronage; Book 3 8 – speaks of freedmen and of Tertullian and Orphician senatus advisers; Book 39 – about the erection of new structures, about the retention of rainwater and about publicans and taxes; Book 40 – slaves, a secret agreement and the right of golden rings; Book 41 – about the acquisition of ownership of a thing and the possession of a thing; Book 42 – about court decisions, assignment of property, separation and trustees over property; Book 43 – about interdicts, public places and ways, superficies, sources, moving and the Salvian Interdict; Book 44 – about procedural objections; Book 45 – about verbal obligations and about stipulation of slaves; Book 46 – about guarantors, innovations, praetor stipulations and repayment of obligations; Book 47 – about private delicts; Book 48 – about the state criminal courts, the Pompeian laws, the Julius laws, the Fabius law; Book 49 – about appeals and reports, fiscus law, military affairs and peculia ; Book 50 – about the citizens of the municipality, the right of immunity, decurions, decrees issued by the council and other rules of ancient law.

Слайд 51

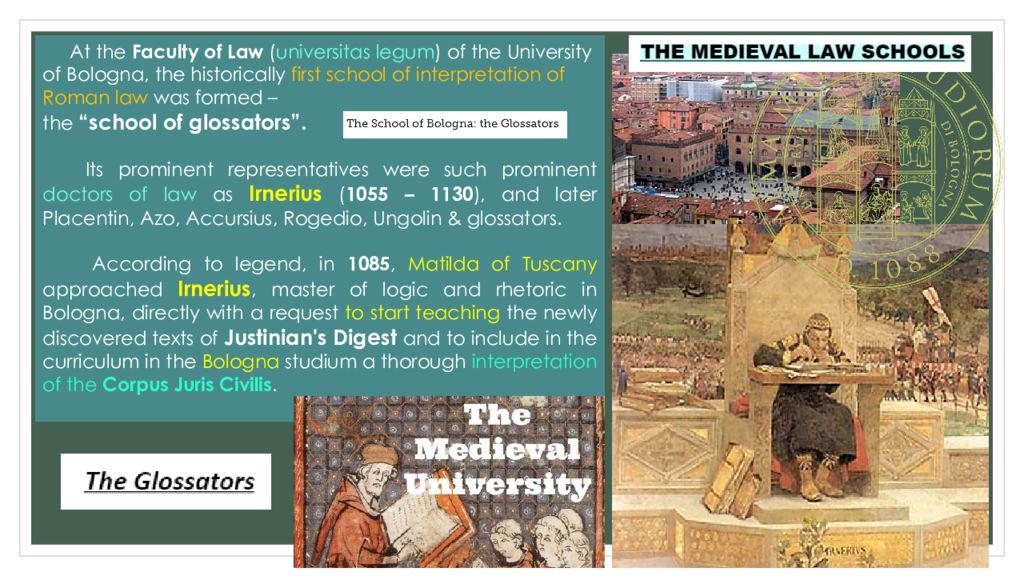

At the Faculty of Law ( universitas legum ) of the University of Bologna, the historically first school of interpretation of Roman law was formed – the “school of glossators ”. Its prominent representatives were such prominent doctors of law as Irnerius ( 1055 – 1130 ), and later Placentin, Azo, Accursius, Rogedio, Ungolin & glossators. According to legend, in 1085, Matilda of Tuscany approached Irnerius, master of logic and rhetoric in Bologna, directly with a request to start teaching the newly discovered texts of Justinian's Digest and to include in the curriculum in the Bologna studium a thorough interpretation of the Corpus Juris Civilis.

Слайд 52

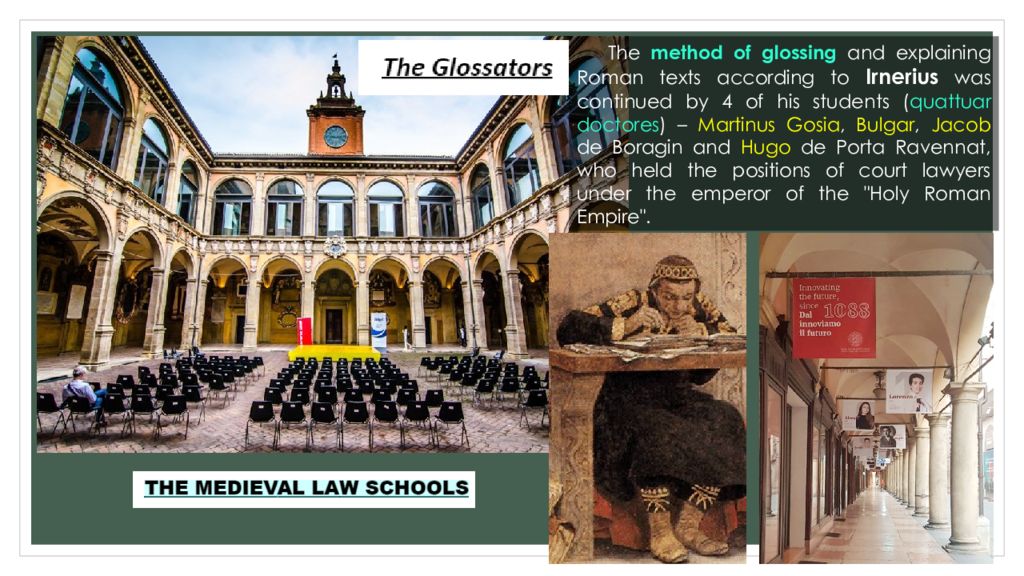

The method of glossing and explaining Roman texts according to Irnerius was continued by 4 of his students ( quattuar doctores ) – Martinus Gosia, Bulgar, Jacob de Boragin and Hugo de Porta Ravennat, who held the positions of court lawyers under the emperor of the " Holy Roman Empire".

Слайд 53

The most celebrated and brilliant lecturer of the Four Doctors was Bulgarus, who was called “ mouth of gold ” (os aureum ). Bulgarus and Martinus were the leaders of two opposing schools at Bologna, corresponding in many respects to the schools of the Sabinians and Proculians during the Roman Principate. Bulgarus adhered more closely to the letter of the law than Martinus. According to Bulgarus, the interpreter should look for the purpose of the law ( ratio legis ), taking into consideration other texts related to the same topic as necessary. According to Martinus, by contrast, equity could modify the apparent meaning of a rule when considering the Corpus Iuris as a whole. Therefore, he thought, all texts that can illuminate the legal problem should be consulted and analyzed. Bulgarus’s approach eventually prevailed.

Слайд 54

Bulgarus was succeeded as a leader of the School of Bologna by his pupil Johannes Bassianus, who believed that the right analysis of a text required four steps : fixing the problem ; finding contrary texts and analyzing the suggested solutions ; finding the general rules or brocards to be applied ; and holding final public discussion of the topic. The Italian jurists Matteo Gribaldi Moffa (c. 1505–1564 ) summed up the method of the glossator in a famous Latin couplet : praemitto, scindo, summo, casumque figuro / perlego, do causas, connoto, et obiicio : “I introduce the problem, I analyze it, I summarize it, and I frame the case / I read through the text, I set my arguments, I remark on other points, and I discuss objections”.

Слайд 55

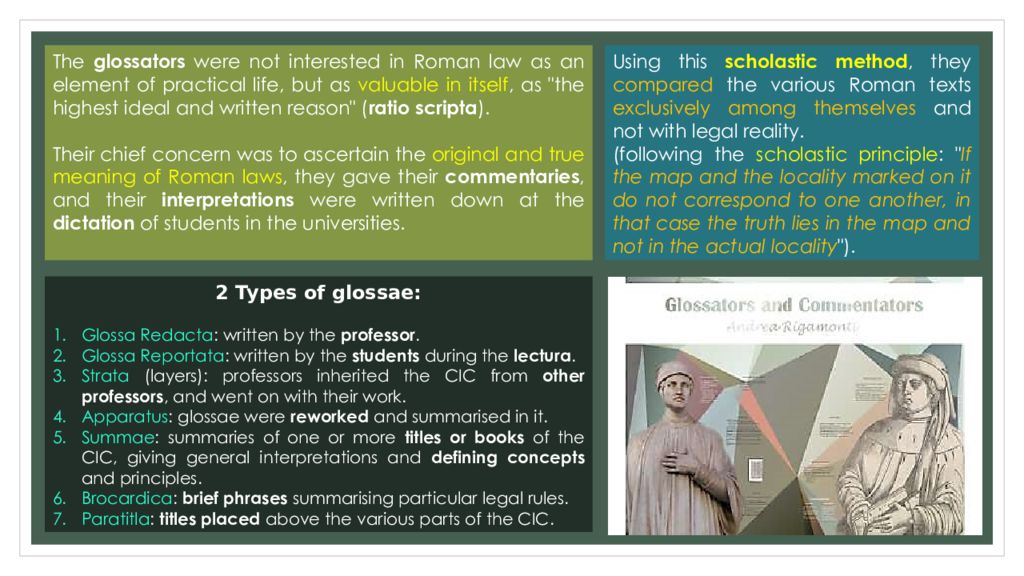

The glossators were not interested in Roman law as an element of practical life, but as valuable in itself, as "the highest ideal and written reason" ( ratio scripta ). Their chief concern was to ascertain the original and true meaning of Roman laws, they gave their commentaries, and their interpretations were written down at the dictation of students in the universities. Using this scholastic method, they compared the various Roman texts exclusively among themselves and not with legal reality. ( following the scholastic principle : " If the map and the locality marked on it do not correspond to one another, in that case the truth lies in the map and not in the actual locality "). 2 Types of glossae: Glossa Redacta : written by the professor. Glossa Reportata : written by the students during the lectura. Strata (layers): professors inherited the CIC from other professors, and went on with their work. Apparatus : glossae were reworked and summarised in it. Summae : summaries of one or more titles or books of the CIC, giving general interpretations and defining concepts and principles. Brocardica : brief phrases summarising particular legal rules. Paratitla : titles placed above the various parts of the CIC.

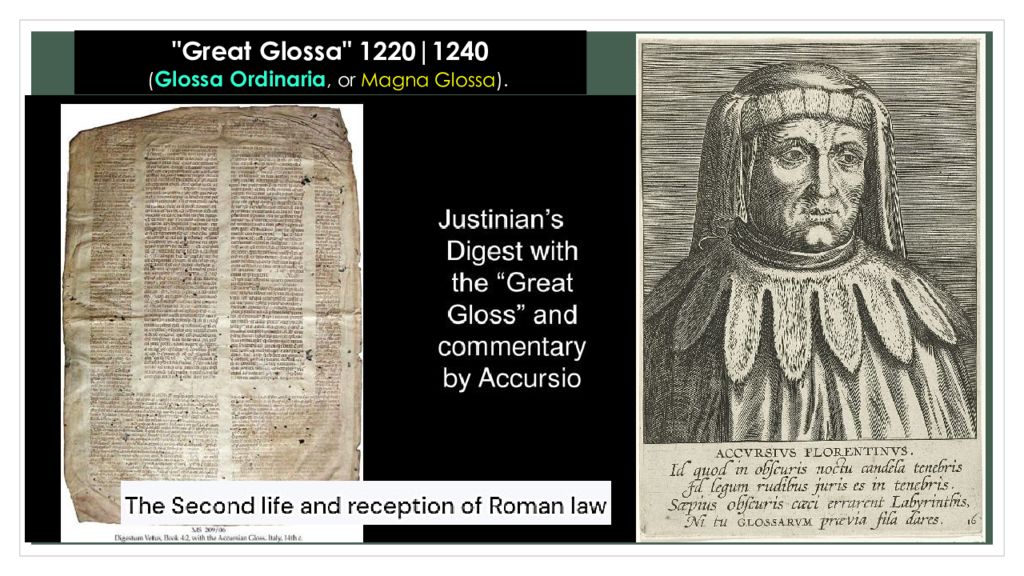

Слайд 56

The glossators collected their observations and comments in the form of special Summas (as general interpretations of the Digest and other parts of Justinian's code, e.g., Placentinus and Azo's Summa Codicem) and Abbreviations (as collections of legal rules for specific casus ). A famous pupil of Dr. Azo, the Florentine jurist-glossator Accursius Florentinus ( 1182 – 1263 ), who taught at the University of Bologna and was nicknamed during his lifetime the " idol of lawyers " (advocatorum idolum), published his "Great Gloss " ( Glossa Ordinarie, or Magna Glossa). In its pages he collected about 97,000 of the best glosses of his predecessors and contemporaries as comments on the texts of Justinian's Code. Subsequently a rule developed in European courts, " what the Glossa ordinaria does not recognize, the court does not recognize either," and the Glossa Accursia itself was used in legal practice until the XVIII th century.

Слайд 59

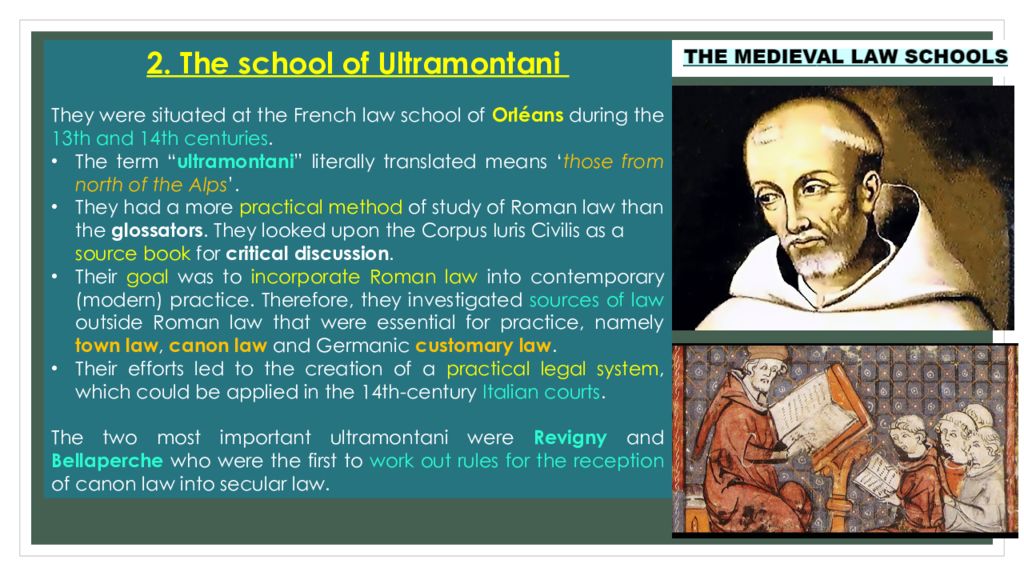

2. The school of Ultramontani They were situated at the French law school of Orléans during the 13th and 14th centuries. The term “ ultramontani ” literally translated means ‘ those from north of the Alps ’. They had a more practical method of study of Roman law than the glossators. They looked upon the Corpus Iuris Civilis as a source book for critical discussion. Their goal was to incorporate Roman law into contemporary (modern) practice. Therefore, they investigated sources of law outside Roman law that were essential for practice, namely town law, canon law and Germanic customary law. Their efforts led to the creation of a practical legal system, which could be applied in the 14th-century Italian courts. The two most important ultramontani were Revigny and Bellaperche who were the first to work out rules for the reception of canon law into secular law.

Слайд 60

Methods of the Ultramontani They adopted a dialectical approach to the study of the Corpus Iuris Civilis (CIC). This means that they regarded the CIC as a source book for critical discussion and not as a rigid system of rules to be accepted unquestioningly. Sources used Corpus Iuris Civilis. Town law (the laws applied by each sity ). Canon law. Germanic customary law.

Слайд 61

The glossators ’ method and teaching style, based on logic & rhetoric, formed the foundation of European legal theory for centuries. It can be said that the glossators were the fathers of European jurisprudence. At the heart of European jurisprudence lies the idea, supported by the glossators, that the legal application of an intellectual rationale in the administration of justice, and not the use of force, is the best path for resolving conflicts between and among humans and nation-states. The glossators considered the law more closely related to logic than to ethics. They did not use logic to test the validity of the argument provided by the text, but to harmonize divergences and clarify truths that they considered suprarational in character.

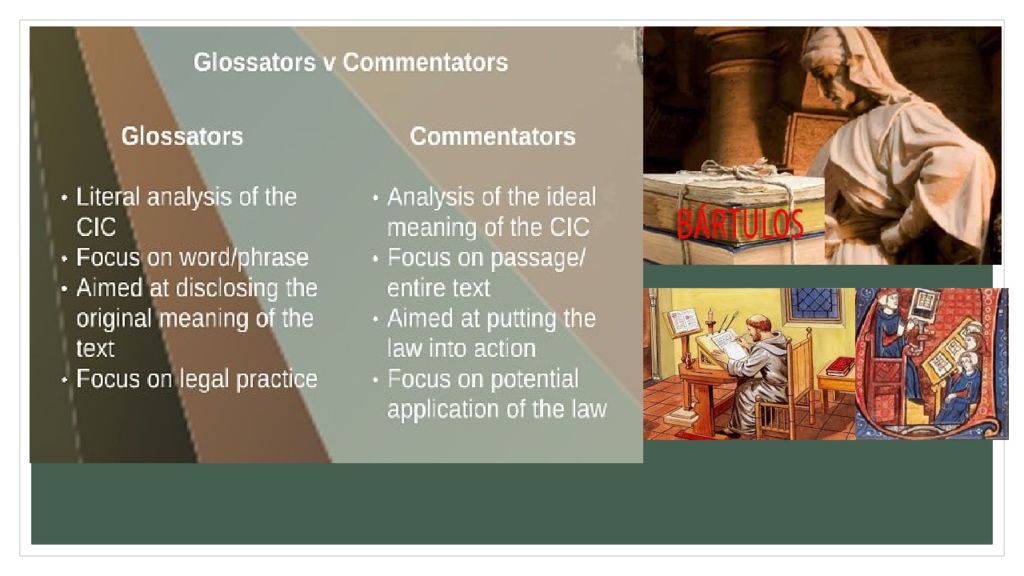

Слайд 62

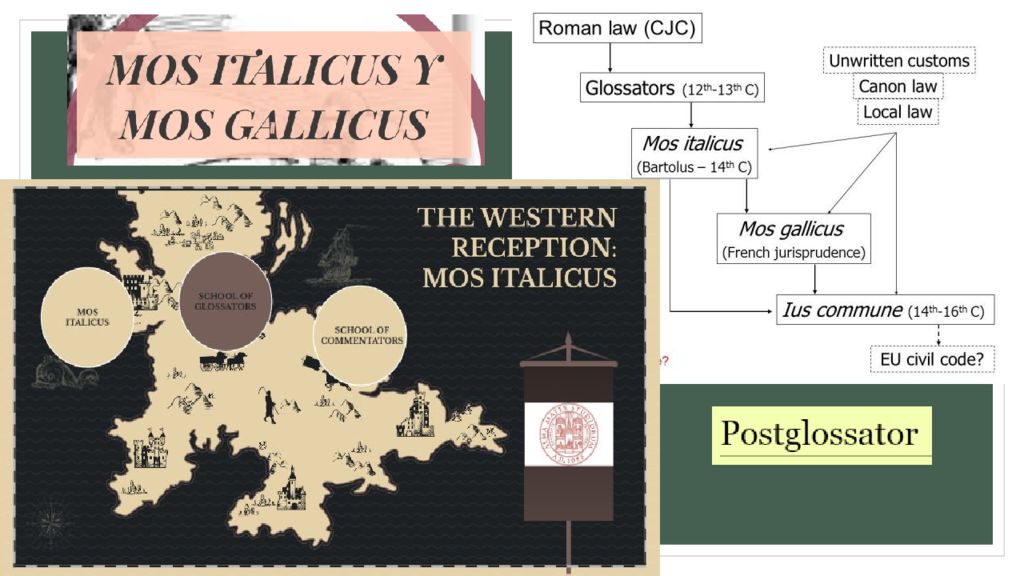

3. The school of Commentators Successors to the ultramontani. Movement started in Italy in the 13th century. After the 12th century the needs of practice became more important to legal scholars. The commentators thus became more concerned with practical aspects of the law than with substantive Roman law. Methods of study: Scholastic method of study adopted. Each commentator gave his opinion on the text of the CIC and also referred to the views of other writers in the same subject. Then to distinguish himself from other writers, he would make finer distinctions and raise entirely new questions. They brought about a synthesis between Roman law, Germanic law, canon law and town law. The method used by the commentators of interpreting Roman law led to its being adapted to contemporary conditions.

Слайд 63

To replace the glossator method of processing Roman texts in the middle XIII – XV centuries comes the scholastic method of the new school of civil law commentators – this is the “ school of post-glossators ” ( conciliators or bartholists ). The founders were the Benedictine monk, the Frenchman Jacques de Ravigny (1230–1296) and the Spanish philosopher Raymond Lull iy (1234–1315). The aim of this school of scholars-practitioners, in contrast to the theorists-glossators, was the systematic adaptation of authoritative sources to the practice of urban and seigneurial courts.

Слайд 64

The work of the Glossators is important for the following reasons: As a result of their studies Roman law spread to other parts of Europe. The work of the glossators ensured the survival of Roman law.

Слайд 65

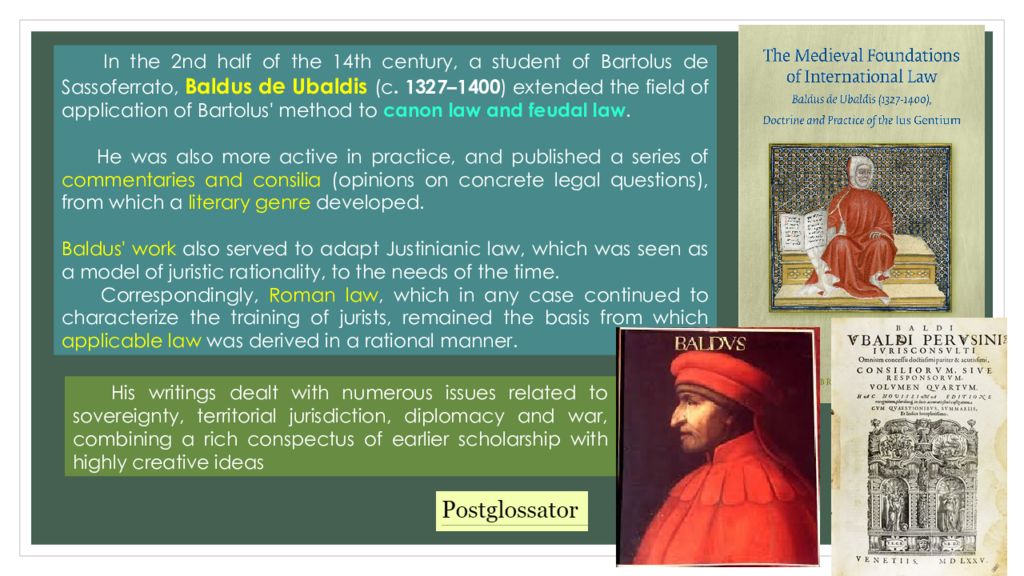

Representatives of the Bartholist school substantiated the idea that any particular provisions of law can and should be deduced from certain universal and indisputable principles. They were attracted by the interpretation itself, and not by the original Roman texts, so they engaged in controversies and wrote glosses to glosses (" glossarum glossas scribunt "). They brought into jurisprudence from the philosophy and science of theology the scholastic method, often used such scholastic techniques as formalized and very tedious divisions : distinctiones and subdistinctiones, divisiones and subdivisiones, ampliationes and limitationes. The most famous among the post-glossators were Sinus de Pistoia (1270-1336), Bartolo de Sassoferato (1313-1357), Baldus de Ubaldis (1347-1400) and other Italian and Spanish legal practitioners. 1270 – 1336 Cinus de Pistorio i n his work “ Lectura super Codice ” made for the first time systematic use of the program of the Commentators.

Слайд 67

The commentators faced head on the conflict of law with custom as they saw the potential for practical application of the Roman law. Many of their ideas were based on practical morality, bold construction of the law and clever interpretations. This made Roman law more flexible, although was clearly a move away from the texts, and thus made it of greater practical use to rulers who were seeking a rational and coherent law. For example, Roman law said that a will was valid if you had 5 witnesses and that Roman law superseded customary law, whilst Venice law only required 3 witnesses. Bartolus ’ approach was to consider why Roman law superseded custom. He concluded that this was because custom was presumed bad. However, in certain circumstances, custom would be allowed by the Emperor, where the law was considered good.

Слайд 68

Bartolo de Sassoferato (1313 – 1357) Bartolus (a pupil of Cinus de Pistorio ), who lectured in the first half of the 14th century in Pisa and Perugia, wrote detailed commentaries on each part of the Corpus Iuris. In his works, he not only presented the opinions of previous jurists, but as a rule developed a position of his own, which frequently broke with tradition and prevailed over the Glossators.

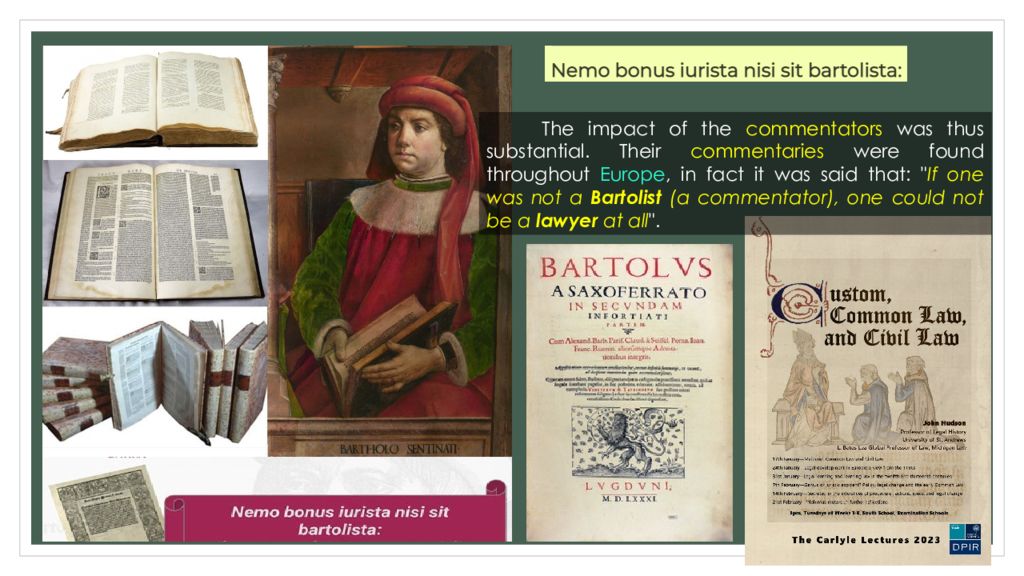

Слайд 69

The impact of the commentators was thus substantial. Their commentaries were found throughout Europe, in fact it was said that : " If one was not a Bartolist (a commentator ), one could not be a lawyer at all ".

Слайд 71

In the 2nd half of the 14th century, a student of Bartolus de Sassoferrato, Baldus de Ubaldis (c. 1327–1400 ) extended the field of application of Bartolus ' method to canon law and feudal law. He was also more active in practice, and published a series of commentaries and consilia ( opinions on concrete legal questions ), from which a literary genre developed. Baldus ' work also served to adapt Justinianic law, which was seen as a model of juristic rationality, to the needs of the time. Correspondingly, Roman law, which in any case continued to characterize the training of jurists, remained the basis from which applicable law was derived in a rational manner. His writings dealt with numerous issues related to sovereignty, territorial jurisdiction, diplomacy and war, combining a rich conspectus of earlier scholarship with highly creative ideas

Слайд 74

IUS COMMUNE – From the 12 th to end of the 15 th centuries AD a common law was built up in Western Europe, the European ius commune, which was based on Roman law, canon law and customary law. It came about when Roman law and canon law were received into the Germanic customary legal systems. Roman law and canon law were adapted to meet the needs of the individual countries. The European ius commune is the historical foundation of most of the countries in Western Europe. The Glossators, Ultramontani and Postglossators all played a role in the creation of the ius commune.

Слайд 75

4. The school of Humanism Italy was the main centre of learning in the Middle Ages, but slipped into the background from the beginning of the 16th century AD. The main centre was then France from the beginning of the 16th century, then the Netherlands and finally Germany. • France and legal humanism from 16th century AD. Their aim was (in contrast to the method of the medieval law schools, who studied the Corpus Iuris Civilis in fragments) to rediscover classical Roman law as it was before Justinian codified it and to study the law as a system. They focused on the Corpus Iuris Civilis and on sources of Roman law that dated before the Corpus Iuris.

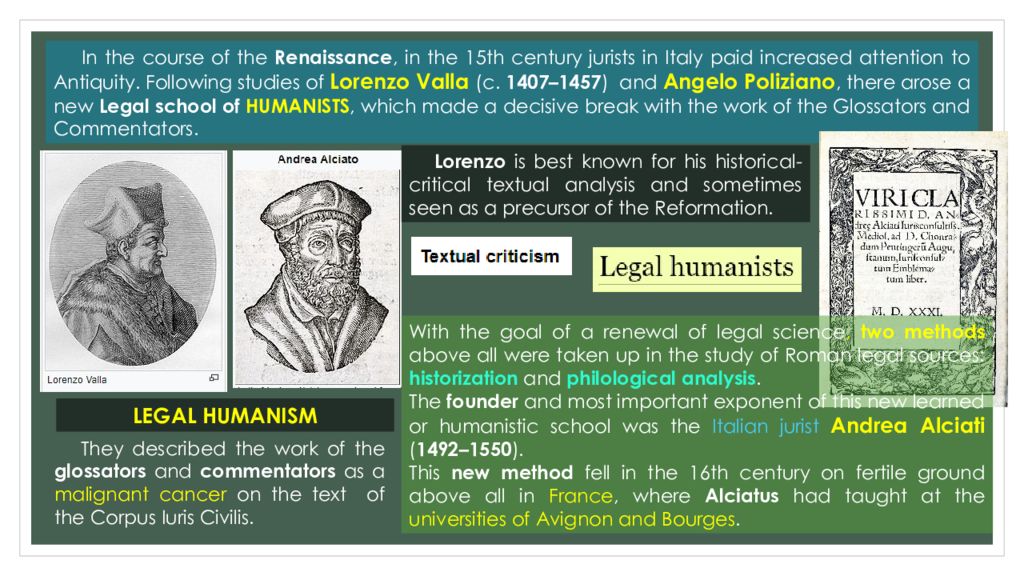

Слайд 76

In the course of the Renaissance, in the 15th century jurists in Italy paid increased attention to Antiquity. Following studies of Lorenzo Valla (c. 1407–1457 ) and Angelo Poliziano, there arose a new Legal school of HUMANISTS, which made a decisive break with the work of the Glossators and Commentators. With the goal of a renewal of legal science, two methods above all were taken up in the study of Roman legal sources : historization and philological analysis. The founder and most important exponent of this new learned or humanistic school was the Italian jurist Andrea Alciati ( 1492–1550 ). This new method fell in the 16th century on fertile ground above all in France, where Alciatus had taught at the universities of Avignon and Bourges. Lorenzo is best known for his historical-critical textual analysis and sometimes seen as a precursor of the Reformation. They described the work of the glossators and commentators as a malignant cancer on the text of the Corpus Iuris Civilis. LEGAL HUMANISM

Слайд 77

This school, the most important exponents of which were Hugo Doneau ( 1527–1591 ) and Jacques Cujas ( 1522–1590 ), was distinguished by a strict rejection of the method and the prolixity of medieval jurists, particularly the Commentators. Instead, the humanist scholars strove for a clear and systematically self-contained account, and additionally for independence from the judgment of medieval jurists. Their aim was a " return " to Antiquity, with which went a particular esteem for classical law. With the aid of a new philological method, they attempted to recognize the manipulations ( called " interpolations " or also " Tribonianisms ") of the Justinianic compilers and to restore the purity of the classical legal texts in their original sense. LEGAL HUMANISM

Слайд 78

Jacques Cujas was a French jurist, born at Toulouse in 1522, where he did all his studies. However, he did not neglect law, and he became lecturer in charge of Justinian’s Institut ion es at the University of Toulouse in 1547. 10 volumes in folio in Latin are the result from his long and brilliant career, which was devoted to the humanist reform of legal studies ( Cujas 1658 ). This was the time of the Renaissance in Europe, and the religious reformers sought a return to the pure Word. In law, the humanists were a parallel movement, seeking a return to classical Roman law. This involved purifying the texts. Cujaccius recognized the importance of studying the best and most original text, and thus used the Florentine manuscript of the CIC. This enabled a better study of the interpolations of these text. LEGAL HUMANISM

Слайд 79

However, as more and more interpolations were revealed, the quasi-Biblical status of the texts was undermined, which undermined the work of the humanists. Since the Renaissance humanists were primarily concerned with a return to classical society, they were not solely interested in the law, but instead in the historical context. Some humanists placed little emphasis on the law except in respect to what it revealed about the Roman society. Pure law was thus given a monumental status. However, this resulted in a move away from practical application of the text. It was recognized that Roman law was the product of Roman society. Cujas, the greatest of legal humanists, had begun to publish one of the great classics of legal humanism, his “ Observations and Emendations ”, a brilliant collection of legal, linguistic, and historical criticisms which grew to monumental proportions in the next forty years.

Слайд 80

The humanists had little impact on the immediate practice of law. Court advocates and notaries remained faithful to the work of the commentators had been better circulated, and they had a vested interest in ensuring that they remained the basis of the court system. Humanism was largely irrelevant since it was based around the discovery of pure Roman law, and pure Roman law was only appropriate for Roman society. However, humanism i n the long term did significantly influence legal science : 1) The principle of using the best available text was established and the quasi-biblical authority of the texts was undermined, resulting in the rise of legal science. 2) The systematisation of the texts was both aided and encouraged, giving rise to the Pandectist school. 3) The logical skills of the humanists in their search for interpolations meant that lawyers had skills that were useful for society as a whole. 4) They were thus the natural mediator in Italy when there was no emperor (and they had Imperial authority ), they created a comprehensive system of law. 5) When in French the church and crown were opposed, the humanists were able to help the king gain control with their use of logic.

Слайд 81

LEGAL HUMANISM Since this school was particularly successful in France, its method became known, although it had originated in Italy, as mos Gallicus (" the French style "). In distinction to this, the previous school of Commentators was termed mos Italicus (" the Italian style "). This success was contributed to by a growing French self-confidence, which also showed in an increased interest in the history and the institutions of France, together with a growing importance of droit coutumier ( customary law). Following the historization process, the practice of Roman law became less important for French jurists. It became general opinion that Roman law had meanwhile lost the character of an eternal and unchangeable model of justice. There developed a resistance, indeed a thorough-going hostility, to Roman law which is reflected in François Hotman's ( 1524–1590 ) polemical work “ Antitribonianus ” ( written 1567 ).

Последний слайд презентации: The history of MEDIEVAL EUROPIAN law

Explain the belief in the Corpus Juris Civilis as a divinely inspired book. How many books did Justinian's Digest contain? Name some book titles. Explain how the Roman law ‘ travelled back ’ to Western Europe after 6 centuries. What method did the Glossators use to annotate the Corpus Juris Civilis ? Explain how legal education ensured the reception of Roman law. What role the Roman Catholic Church played in the reception of the Roman law. Explain the main contributions of the school of the Commentators. What methods did the Commentators use ? What does the term mean “ mos italicus ”? Why were they called bartholists and conciliators ? How did the Commentators ensure the reception of Roman law in Western Europe? Explain the method & contributions of the School of the Legal Humanists. You must also name three humanist lawyers. Explain why the civil law Legal system forms the South African / Louisiana / Scotland / Quebec mixed legal system. We are writing ( printing ) a review essay on the topic "RECEPTION of Roman law in Europe"